Following the spirit of the age, Duke James wished to enlarge his trading area and obtain colonial possessions in various parts of the world. In the mid-1640s he began to consider sending ships to Guinea, as the whole of the coast of Africa from Cabo Verde to Niger was known at the time. In 1651, the duke’s representatives managed to get the native chiefs to grant them bases at the mouth of the River Gambia: St Andrew’s Island (now Kunta Kinteh Island, about 30 km from where the river enters the Atlantic Ocean), where he built a fort, as well as the village of Jillifree on the right bank of the river opposite St Andrew’s Island (present-day Jufureh) and Bayonne (the present Gambian capital Banjul). The duke’s trading posts continued in existence until 1659, when the Dutch seized them, taking advantage of the duke’s imprisonment by the Swedes. In 1660 the duke’s people regained the trading posts, but already in March 1660 they were taken over by the English.

Exactly how Duke James obtained the right to the island of Tobago in the West Indies is still not clear. Tobago had seen previous unsuccessful colonization ventures by the Spanish, French, English and Dutch. Duke James’s first colony on Tobago was established in 1654. That same year, colonists sent by Dutch merchants, the Lampsins (also Lamsins) brothers, arrived on the island. From this time onwards, there was competition between the Courlanders and the Dutch, the latter gaining the upper hand, because Duke James’s plans were largely disrupted by the Polish–Swedish War.

On his return from captivity, James strove to regain his colonial possessions, but without much success. In an agreement concluded with England in 1664, the duke renounced his claim to his trading posts in Gambia in favour of the English, receiving in return the right of free trade in the king’s dominions in Guinea. However, the Royal African Company had no wish for competition and refused to admit the duke’s ships into English-controlled ports. All of the duke’s later attempts to regain Gambia remained fruitless.

Although the King of England had confirmed James’s right to Tobago in the agreement of 1664, the Dutch remained the real masters of the island. Several expeditions sent by the duke did not reach the island for various reasons, and those that did encountered great difficulties. A second Courlander colony was established in about 1680, and this, too, existed for only about 10–15 years. Moreover, because of pirate attacks and military conflict between the great powers, the Europeans abandoned the island for several decades at the beginning of the 18th century. However, at a political level the Dukes of Courland claimed sovereignty over Tobago right up to the abolition of the duchy.

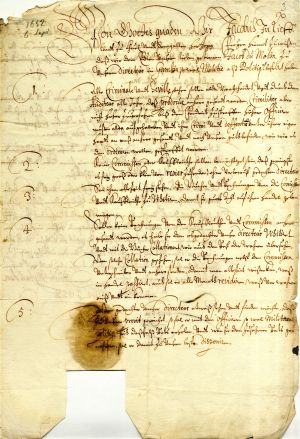

1. Letter from Duke James to Franz Hermann von Puttkamer, Duchess Louise Charlotte’s chamberlain. Mitau/Jelgava, 16 October 1651. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 2, file 2982, p. 1.

Puttkamer had been sent on a diplomatic mission to the Netherlands. Among other tasks, he was to obtain an answer from the East India and West India companies to Duke James’s proposal to engage in joint trading activities in the overseas territories. James pointed out that the Dutch would benefit greatly from such an agreement, since the duke planned to sell the colonial goods in Holland. On the other hand, rejection of the offer would be no barrier to James, and he would be sending his ships to the East and West Indies in any case.

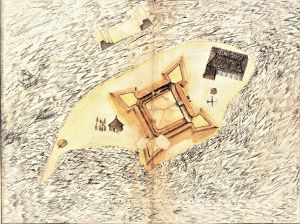

2. Duke James’s fort, which was to be built on St Andrew’s Island in the mouth of the River Gambia. 1651. Ink and watercolour. LVVA, collection 7363, inventory 3, file 111, p. 553.

The first ships to reach the mouth of the River Gambia, in late October 1651, were the Crocodill (Crocodile) and the Wallfisch (Whale). The expedition was led by the Dutch captain Peter Schulte, who was familiar with the coast of Guinea, and Major Joachim Denniger, born in Goldingen/Kuldīga. Most of the soldiers and seamen had been recruited in Copenhagen. The fort was evidently designed by one of the participants in the Courlander expedition. This drawing was previously unknown to researchers, although an image of the fort as it had actually been built, depicted in a similar style, has been published in the historical literature.

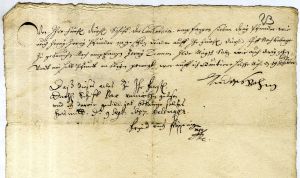

3. Letter from Pastor Gottschalck Ebeling to Duke James. Gambia Island in Africa, 20 March 1652. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 521, pp. 157–158.

Ebeling tells of how the duke’s ship Crocodill encountered the ships of prince Rupert of the Rhine, Duke of Cumberland (Ruprecht von der Pfalz, 1619–1682, referred to in the letter as Robert) in the mouth of the river Gambia. They were privateers preying on English Parliamentarian and Spanish ships. Rupert had revealed to the Courlanders that gold could be obtained from two of the tributaries of the Gambia. Accordingly, Ebeling suggests to the duke that he might send some strong ships and yachts for navigating the river. At the same time, the pastor accuses Peter Schulte, captain of the Crocodill, of betraying the duke’s interests, possibly because there was strife between the two men.

In contrast to Schulte, who returned to Courland in summer 1652, pastor Ebeling remained in Gambia, where he died soon afterwards. It should be added that an erroneous form of the name, Eberling, has become established in the historical literature.

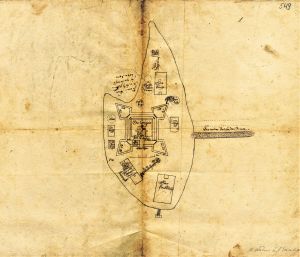

4. The trading post and fort of the Duke of Courland on St Andrew’s Island in the mouth of the River Gambia. Early 1650s. Ink. LVVA, collection 7363, inventory 3, file 111, p. 549.

The plan shows a sketch of the situation on St Andrew’s Island following the building of the fort. The fort has four bastions with two cannon on each; in the surrounding area there was a storehouse, dwellings for the trading agent, the captain and the soldiers, as well as a bread oven. A church was also built, next to which there was a cemetery and a pastorage. A possible salt production site is also marked.

The plan displayed here was previously unknown to researchers.

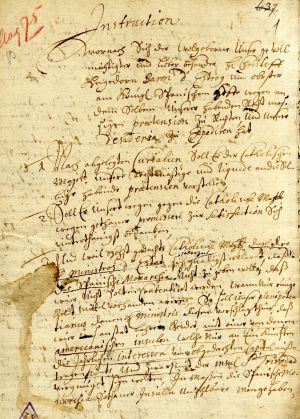

5. Instruction from Duke James on the appointment of Jacob du Moulin (also du Mollin, Mollihn) as director of the Gambia colony. Mitau/Jelgava, 6 September 1652. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 2, file 2982, p. 3.

In his instruction, the duke lists Du Moulin’s functions and the scope of his powers, granting him jurisdiction in civil and criminal matters, and giving him complete control over the activities of the duke’s trading agents. James also indicates that the Courlanders are not to show any aggression, but in case of attack should defend themselves to the last man. Du Moulin was to spend three years in Gambia, for which he was to be paid 120 thalers a month.

Du Moulin’s expedition included the ships Patientia (Patience) and Crocodill, which arrived in Denmark in late October 1652. Du Moulin and the other members of the expedition spent nine weeks in Denmark, preparing the ships for the voyage, but because of storms and a shortage of provisions, they were forced to return to Courland without reaching Gambia. Jacob du Moulin was put on trial and spent almost two years imprisoned in Goldingen/ Kuldīga Castle.

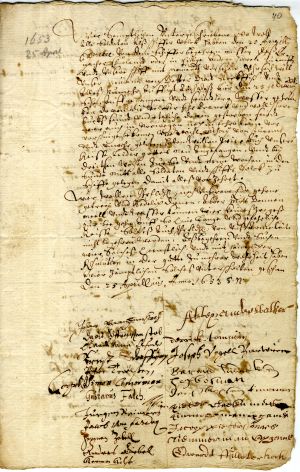

6. Submission to the duke from the crew and soldiers of the ship Patientia. [Faeroe Islands], 25 April 1653. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 2, file 2982, p. 40.

The ships of Du Moulin’s expedition sailed from the Öresund on 25 January 1653, and after spending ten weeks on a stormy sea, called at the Faeroe Islands in early April. Here, strife continued between Jacob du Moulin and the other officers, having begun already in Denmark. Because of the lack of decent food, the crews and soldiers also began to mutiny.

A letter signed by 87 people states that they had demanded that the captain take the ship to Courland, because they were already out of butter, bread, fish and other produce and there was no possibility of augmenting the provisions, but it was impossible to go on such a long voyage when only flour and beans remained. They had also run out of beer, and many were ill and some had even died from drinking the water. They would be happy to serve the duke, but not under such conditions.

The Patientia returned to Windau/Ventspils in May 1653 but soon set sail for Gambia once again, although this time without Du Moulin, who had already been put on trial.

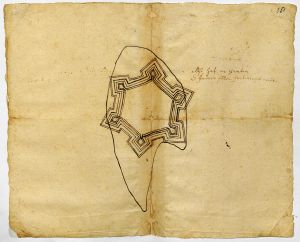

7. Sketch of a design for the Gambia fort. 1650s. LVVA, collection 7363, inventory 3, file 111, p. 551.

Along with drawings that show the actual situation on St Andrew’s Island in Gambia, the document collection also includes a sketch of one version of the design for the fortifications on the island. Unfortunately, it is not clear whether this design was drawn before building work on the fort began and remained unrealized, or was intended as a design for alterations to the already existing fort.

This drawing, too, was previously unknown to researchers.

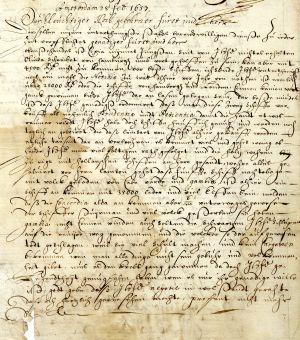

8. Letter from factor Henry Momber to Duke James. Amsterdam, 28 February 1657. Copy. LVVA, collection 7363, inventory 3, file 439, p. 11.

Momber repeats the suggestion he had put forward already in a letter on 17 February that the ships Prudentia (Prudence) and Patientia should be sold. He considered it would be more profitable for the duke to undertake timber exports in Dutch ships from the port of Riga. Apart from this, Momber reports that a ship had arrived in Amsterdam, the captain of which had reported encountering the duke’s ship Concordia (Concord) in Gambia. It had spent more than half a year on the voyage, and a large part of the crew, including the captain and helmsman, had died.

9. Report from Captain Otto Stiel (also Styl), commander of the Duke of Courland’s base in Gambia. London, 13 December 1661. Transcript. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 2, file 2982, pp. 56–57.

The information when the Courland-born Stiel became Governor of Gambia is contradictory, but it is definitely known that this occurred after the death of Joachim Denniger, who had arrived in Gambia a second time.

The report tells of events in 1659–1661, when, taking advantage of James’s incarceration by the Swedes, the Dutch and English took over the duke’s possessions in Gambia. First, in 1659, representatives of the Amsterdam Chamber of the West India Company (WIC) convinced the garrison of the fort on St Andrew’s Island to leave, asserting that because the duke was a prisoner they had no hope of receiving their pay. The mutinous soldiers arrested Stiel and handed over the fort to the Dutch; he himself was also forced to leave for Holland. There he received word that the fort had been plundered by French corsairs. After this, the fort was taken over by the WIC Groningen Chamber, which returned it to the Courlanders. Stiel returned to Gambia in June 1660, but three weeks later the fort was attacked by ships of the WIC Amsterdam Chamber, forcing Stiel to surrender. Since they did not receive support from the natives, the Dutch abandoned the fort a month later. Stiel continued his activities up to March 1661, when a squadron of ships of the King of England, commanded by Robert Holmes, took over the fort, and the Courlanders were forced to leave St Andrew’s Island yet again – this time, never to return.

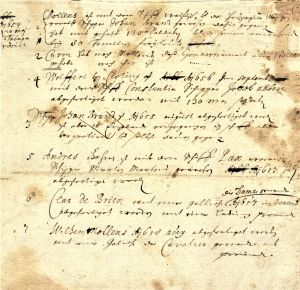

10. List of the duke’s ships sent to Tobago. About 1661/1662. Author unknown. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 287, p. 128.

This list constitutes one of the few pieces of authentic evidence held at the Latvian State Historical Archives concerning the Courlanders’ activities on the island of Tobago during the first period of James’s rule. It records that on 20 May 1654 Tobago was reached by Willem Mollens on the ship Wallfisch (Whale) and the captain Johann Brandt on the Wappen der Herzogin von Kurland (Coat of Arms of the Duchess of Courland), bringing 120 soldiers and 80 families of freemen. After Mollens, a certain Caron served as governor for a time. He was followed by Wollfert von Clotting with 130 soldiers, brought in September 1656 by the ship Constantia (Constancy), captained by Jacob Alberts. In August 1655, the captain Johann Brandt was sent out (again), but he landed in England and abandoned the ship. In July 1657, Andreas Bohm was sent to Tobago with the ship Pax (Peace) under captain Marten Martens. In December 1657, Clas de Brien was despatched to the island on the galiot Die Dame (The Lady), bringing a cargo of foodstuffs. Willem Mollens was sent out in August 1658 on the galiot Der Cavalier (The Cavalier), with a cargo of provisions.

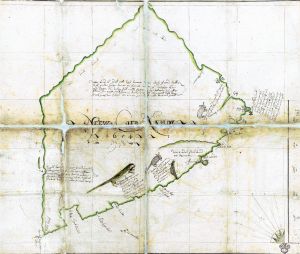

11. Map of the island of Tobago. 1654. Ink and watercolour. LVVA, collection 7363, inventory 3, file 111, p. 545.

The map was drawn by one of the first colonist sent by James, who arrived on Tobago in May 1654. The colonists named the island New Courland (Neew Coerlande). The map is oriented south–north, and the annotations are in Dutch. It was compiled in the period up to 11 August, when Willem Mollens wrote to James that he was sending him a small map. The contours of the island are drawn very approximately, and it is clear that the Courlanders had not yet charted it in full, but Mollens asserted that there were no Europeans on the island. The only habitations marked on the island are Fort James (Jacobo foort) and Windau/Ventspils Village (dorch Windoo), on the shore of what would become known as Courland Bay. Evidently, by the time the Courlanders arrived on Tobago, none of the residents of the Dutch colony existing there in the 1620s–30s were still present, and the colonists sent by the Lampsins, merchants of Vlissingen, arrived no earlier than the autumn of 1654.

The map was previously unknown to researchers and is the oldest securely dated map of Tobago.

12. Plan of Fort James, established on the island of Tobago. 1654. Ink and watercolour. LVVA, collection 7363, inventory 3, file 111.

The plan has been sketched on the back of the map of the island of Tobago. It shows the first steps in the establishment of the colony. The fort was surrounded by earthworks, which had a single bastion. Inside, a building is marked where church services were held. Outside were warehouses, a plantation and a cemetery. Flags of the Duchy of Courland flew above the earthworks.

It may be noted that the documents at the LSHA do not contain any direct or indirect evidence that the Courlanders settled on Tobago earlier than 1654, as is often claimed in the historical literature.

13. Receipt signed by Andreas Bohm, head of the expedition to Tobago, and the duke’s factor Friedrich Pöpping. Helsingør, 9/19 September 1657. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 1026, p. 23.

The ship Pax, captained by Marten Martens and with the former Windau/Ventspils coast bailiff (Strandtvogt) Andreas Bohm on board as commander, sailed from Windau/Ventspils in July 1657. At Helsingør in September the Pax took on nine cannon that had been removed from the Concordia as well as two barrels of salt obtained on the island of Maio and 13½ pounds of lead weights for use on Tobago. The factor Pöpping affirms that these items would be required on the ship. Apart from this, water barrels were transferred to the Pax from the duke’s ship Constantia, which was returning from Tobago.

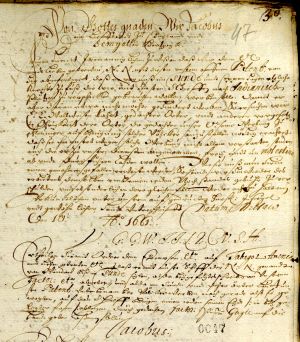

14. Form for a patent and instruction from Duke James. 10 [January] 1661. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 265, p. 47.

The patent is addressed to Danish officials, informing them that the duke has sent the named individual [N.N.] to recruit soldiers on the waterfront of Copenhagen and the Öresund to be sent to America and asking them not to hinder the soldiers from reaching the ships. According to the instruction, the person chosen by the duke was to voyage from Windau/Ventspils to Tobago, stopping at the Öresund, where, in accordance with the issued patent, soldiers were to be recruited, they were to give an oath of loyalty to the duke and were each to be issued with two months’ pay.

These documents testify to Duke James’s desire to re-establish, as soon as possible, his colony on Tobago, which had been taken over by the Dutch in 1659. However, it was actually several years before any of the duke’s ships reached the island.

15. Oath given by the steward Melcher Kuhlman. [Mitau/Jelgava], 5 October 1663. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 389, p. 3.

In certain cases, being sent to the colonies was also instituted as a form of punishment. This is seen, for example, from the oath signed by a steward of the duke named Kuhlman. In the course of his duties, he had misappropriated beer and other produce, which he could not pay for. Accordingly, Kuhlman was arrested, but after the Landhofmeister had interceded with the duke on his behalf, he was released on condition that he would travel to Gambia, Tobago or elsewhere, as instructed by the duke, and would compensate the losses by his labour. Kuhlman promised to be loyal to the duke and fulfil his military duties diligently.

16. Agreement between Duke James and Charles II of England. [London], 17 November 1664 [old style]. Transcript. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 6, pp. 81, 83.

On his return from captivity, Duke James immediately commenced diplomatic activities in order to re-establish his rights to the colonies. However, his only success in this respect was an agreement concluded on 17 November 1664 with Charles II of England. In this agreement, the duke relinquished his right to his forts in Gambia in favour of the English, for which James was given the right to freely trade in the king’s dominions along the coast of Guinea, paying the king the usual 3% customs duty. King Charles also declared that he was granting James the use of Tobago, on condition that it would be colonized only with subjects of the duke and the king, and all trade was to pass through the ports of Courland or England, or through Danzig. However, this agreement did not prove to have great practical significance.

17. Instruction from Duke James to ship’s captain Moritz Castens. Mitau/Jelgava, 3 September 1668. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 850, p. 3.

The memorial supplements an order issued that same day by the duke for Castens (also Carstens) to take the ship Isslandsfahrer (Island Voyager) to the Öresund, where he was to enlist a crew for a voyage to Tobago and help Captain Hans Georg Waltmann to recruit 40 men in Copenhagen for the garrison. Once he arrived on Tobago, Castens was to land Waltmann and his men on the island, while he himself was to go to Barbados, where he was to exchange a cargo of vodka for tobacco, sugar, ginger, cotton and other goods, which he was to bring back to the Öresund. If there was still space on the ship, then he was also permitted to carry other cargoes, for which he was to charge shipping costs. Castens had to send some three cattle, bulls and some calves to from Barbados to Tobago.

However, the expedition did not proceed according to plan. A dispute arose between Castens and Waltmann, and the Courlander fort on Tobago was in the hands of the Dutch, who maintained they had bought it from the previous colonists. Since Waltmann’s forces were too weak to take the fort, they all went to Barbados. There it turned out that most of the vodka barrels were empty. As Moritz Castens subsequently testified, the vodka had leaked out during the voyage, because the barrels had been of poor quality. Thus, the expedition brought the duke considerable losses, while Tobago remained under Dutch control.

18. Instruction to Major Johann de Lech and Lieutenant Robert Bennet (also Banet), whom the duke was sending to Tobago. Mitau/Jelgava, 1 November 1670. Authenticated transcript. First page. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 2621, pp. 12–18.

In this order, Duke James instructs the two officers to govern Tobago jointly, and to develop commerce and plantations to the best of their abilities. The soldiers of the garrison were to serve for three years, the voyage there and back being calculated as lasting one year, while the remaining two years were to be spent on the island. Johann de Lech and Robert Bennet were to conduct a survey of the island and compile a detailed report. James permitted the colonists freedom of religion, allowing them to hold Lutheran, Catholic and Calvinist services, but the slaves that the duke planned to bring were to be converted to Lutheranism. They were ordered to co-exist peacefully with the native population and resort to weapons only in defence.

The instruction shows that James was striving to fulfil the articles of the 1664 agreement on the colonization of Tobago, since De Lech was a Courlander while Bennet was a Scot. There are several documents in which the duke expresses his wish to recruit colonists in Britain. On the other hand, there is no documentary evidence that James sent Latvians to Tobago.

The full text of the instruction and a translation into Latvian has been published in the journal Latvijas Arhīvi, 2018, no. 3. Accessible in digital form on the National Archives of Latvia website.

19. Map of the island of Tobago. About 1687. Photocopy from 1930s. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 2621, p. 89.

The place names on the map bear evidence to the presence of the Courlanders on the island – Jacobi-fort from the name of Duke Jacob (James), Benets bay from the name of Robert Bennet, and Moncks Fort. The latter originated from the name of a colonel of Scottish descent, Franz Monck, who was the last governor appointed by the Duke James and who reached the island after the duke had already passed away.

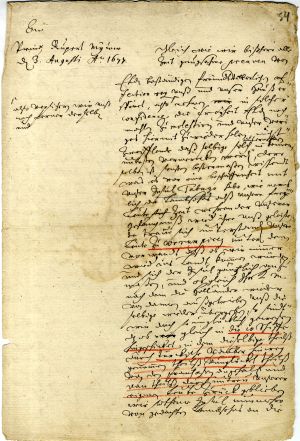

20. Letter from Duke James to Prince Rupert, cousin of the King of England. 3 August 1677. Draft. LVVA, collection 5759, inventory 2, file 1326, p. 34.

In this letter, James expresses his regret that the Dutch are still masters of Tobago, and that the majority of some ten ships sent there by the duke since the agreement [of 1664] had been concluded had not reached their destination because of pirate attacks and betrayal by their own people. James asked Rupert to urge Charles II to take action against the Lampsins and help the duke establish his rights to the island. The duke also asked for Rupert’s support in obtaining passes for Courland ships signed by the Duke of York and the African Company, since otherwise the duke’s ships were forced to turn back without reaching the coast of Gambia.

In spite of the rights to trade in Gambia guaranteed by the agreement of 1664, the officials of the Royal African Company forbade the duke’s ships from visiting the ports under its control, on the pretext that their ships’ passes were not in order. The head of the company was the king’s brother, James Stuart, Duke of York.

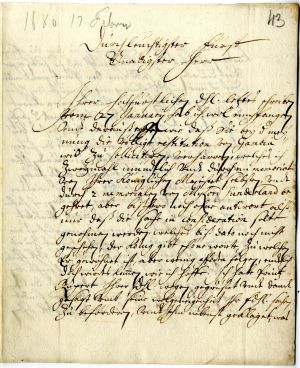

21. Letter from agent Abraham Marin to Duke James. London, 17 February 1680 [old style]. LVVA, collection 5759, inventory 2, file 1326, pp. 43–44.

In reply to a letter from the duke on 27 January, in which James confirms he will work to regain full control in Gambia, Marin writes that he has already discussed the matter with the king twice and has submitted several petitions, but has so far only been promised that the matter would be considered. Prince Rupert had advised him not to put any hopes on the king and instead address the Duke of York, who was in charge of affairs relating to Gambia. He was expected to arrive very soon. In the letter, Marin also lists the wages paid to seamen of the Royal Navy, as he had been requested by the duke.

Up to the very end of his life, Duke James strove to come to an agreement with England that would allow him to regain his former possessions in Gambia. Unfortunately, these efforts remained futile.

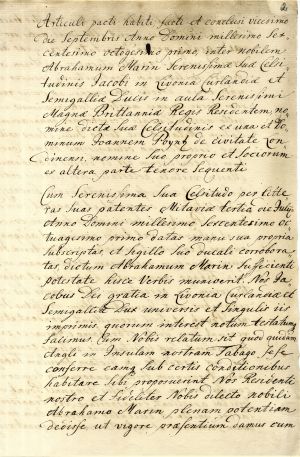

22. Agreement between Duke James of Courland and Captain John Poyntz, subject of the King of England. London, 20 September 1681. [old style]. Transcript. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 388, pp. 2–5.

The agreement was concluded by Abraham Marin, James’s agent in London, in accordance with an authority from the duke. Under the agreement, Poyntz and his companions undertook to send 1200 colonists to Tobago, who were to cultivate the island under the auspices of the Duke of Courland, receiving a total of 120,000 acres of land. Even though James ratified the agreement on 24 October 1681, friction on particular issues continued. For example, the English side wished to appoint a governor of their own, alongside the duke’s governor. Duke James’s death on 31 December 1681 as well as the obstacles created by the English government meant that the agreement remained unfulfilled, even though Poyntz continued to seek its implementation for many years.

It must be said that these plans were rather fanciful, because the land area of Tobago was not as large as indicated in the agreement.

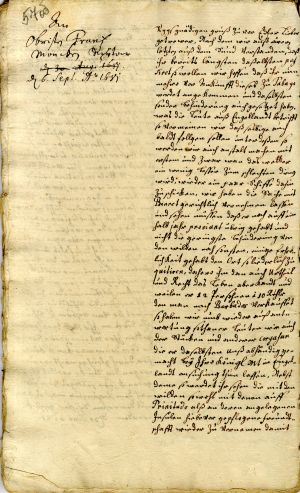

23. Letter from Duke James to Colonel Franz Monck. Mitau/Jelgava, 6 September 1681. Draft. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 449, pp. 57–58.

In reply to Moncks’s letter from Denmark, the duke expresses the hope that the colonel will not tarry there longer but will leave for Tobago. James also explains that he has declared Robert Bennet a wanted man and has sentenced him to death in absentia, because he has abandoned the island without good reason and without the duke’s permission: he had sufficient food for at least another half year, and the local savages had not been causing problems. James had also submitted a request for the English to return to him 12 men of the garrison whom Bennet had sold into slavery in Barbados for 10 thalers each, as well as the duke’s goods and cannon that had been handed over to the English. James orders Monck to be friendly towards the inhabitants of the surrounding islands and trade actively with them. Likewise, Monck was to show civility towards the English colonists who were due to arrive in accordance with the agreement that the duke was preparing to conclude with the English captain John Poyntz and assign them lands between the duke’s plantations.

Franz Monck reached Tobago in late 1681 or early 1682, i.e., around the time of Duke James’s death.

24. Instruction from Duke James to Christoff Hagedorn, Baron d’Estroy, his envoy at the court of the King of Spain. Mitau/Jelgava, 13 August 1675. Transcript. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 724, pp. 1–2.

For many years, James strove to obtain compensation from Spain for the ship Gekröntes Elendt (Crowned Elk), which had been captured near Dunkirk in 1645 by Spanish privateers because it had a Dutch captain. By 1661, the duke was calculating the value of the ship and goods together with interest at 80,000 thaler, and starting from the 1670s he demanded the Spanish possession of Trinidad as compensation.

According to the duke’s instruction, Hagedorn was to request an audience with the King of Spain, in order to thank him for his promise to pay the duke compensation as soon as money was available and propose that instead of payment in cash, the king might grant James the right to the island of Trinidad, located near Tobago, until such time as the duke could compensate his losses. James promises not to hand over Trinidad to any other power and not to hinder the activities of the Jesuits or the Catholic Church as such on the island.

Right up to the final months of his life, the duke continued to hope that Spain would satisfy his request, but his hopes were never fulfilled.

25. Ships of the Duke of Courland by the shores of Gambia and Tobago. Copied from maps of the mid-17th century. LVVA, collection 7363, inventory 3, file 111, pp. 545, 553.

The flags flown by the duke’s ships are clearly visible in the drawings. The colours red and white symbolized Poland-Lithuania as his overlord, and some flags also had an embroidered coat of arms of the duchy. There is no indication in the documents that the flags of the duke ever depicted a black crab, although such a flag appears in tables of ship flags published in Europe in the first third of the 18th century. It has been discovered in the course of recent research that in the years of James’s rule, a coat of arms was created for Tobago, depicting an elephant. Moreover, documents from 1680 also mention a ship with the same name Elephant, which was renamed soon afterwards as the Wappen von Tobago (Coat of Arms of Tobago). Thus, the matter of the crab as a symbol of the duchy is still not resolved. Neither does the black crayfish have any link to the Duchy of Courland: evidently, this is a transformation of the crab, which became popular following the showing of the fictional film Melnā vēža spīlēs (In the Claws of the Black Crayfish; Riga Film Studio 1975, director: A. Leimanis).

It should be noted that a sign with a painted coat of arms of Courland would generally be put up at the gates of the colonial forts, identifying them as belonging to the duke, and the soldiers and colonists would swear an oath to the Duke of Courland. Accordingly, regardless of ethnic background or place of birth, they were all known as Courlanders. This evidently gave rise to the myth that James sent a large number of Latvians to Tobago.