Duke James’s foreign policy was closely linked to his economic activities and his strivings to become involved in the process of world colonization. This is demonstrated by his trading and shipping agreements with France and England, and his attempts to establish himself in various parts of the world. Following a policy initiated by his uncle, Duke Friedrich, James kept the Duchy of Courland strictly to a path of neutrality, which was no easy task, considering the growing ambitions of its neighbours. Reconciling Poland-Lithuania and Sweden became one of the major diplomatic aims of the first two decades of James’s rule. At the same time, it was impossible for him to maintain his status and prestige without strengthening dynastic links and extensive correspondence with the courts of other European rulers.

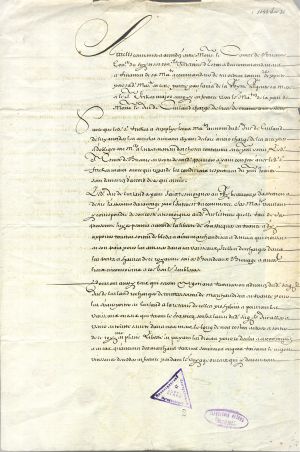

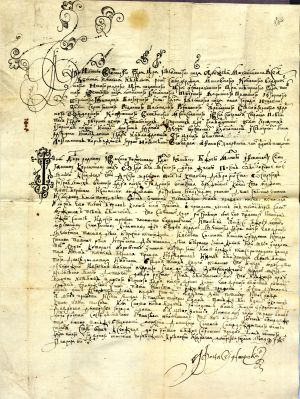

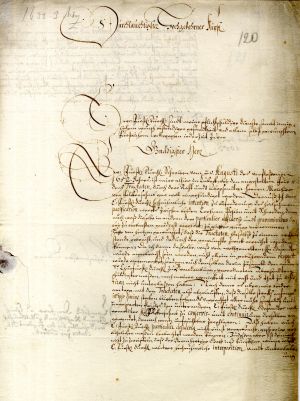

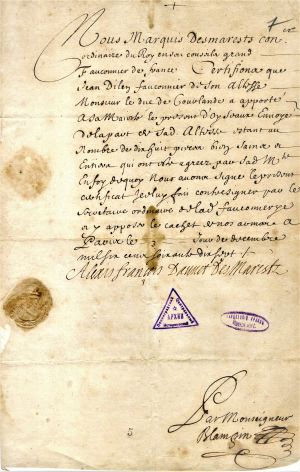

1. Agreement between the Duke of Courland and France. Paris, 30 December 1643. Original. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 676, p. 3.

France was the first country with which Duke James concluded an official international agreement. The duke’s envoy Georg Fircks, who signed the agreement on behalf of the duke, succeeded in getting the French government to grant the duke free trading rights in France, and the duke was permitted to purchase real estate in France. For his part, James gave the French the same rights in the Duchy of Courland and promised he would provide no assistance to the king’s enemies. On the French side, the agreement was signed by foreign minister Henri-Auguste Loménie de Brienne.

2. Letter from Louis XIV of France to Duke James. Paris, 20 January 1646. Original. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 676, p. 45.

In this letter, the seven-year-old Louis XIV expresses his friendship and respect towards the Duke of Courland and promises to ratify the agreement concluded in 1643.

Duke James sent Georg Fircks to France once again in autumn 1645. Among other things, he was asked to achieve ratification of the agreement of 1643. The process was a protracted one, however: the king signed the ratification document only on 16 November 1646.

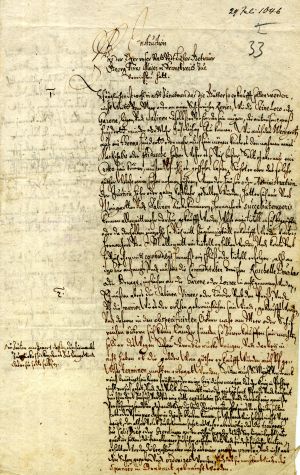

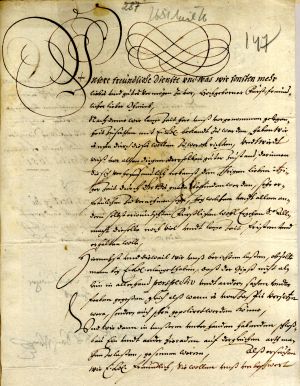

3. Instruction to Georg Fircks, envoy to France. Mitau/Jelgava, 29 July 1646. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 676, pp. 33, 34.

In summer 1646, the duke sent Fircks to France a third time. He was not only to get the agreement ratified by parliament but also to purchase an estate in France for the duke, one that was not far from navigable waterways. The property was to have vineyards and salt mines, and there should, preferably, be a noble title accompanying it, such as marquis. Fircks fulfilled only the first part of the task: the agreement was ratified in parliament on 24 February 1647. However, it was not possible to find a suitable property at an acceptable price.

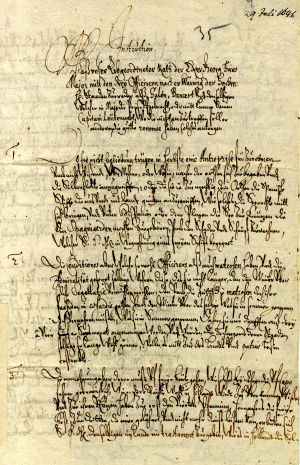

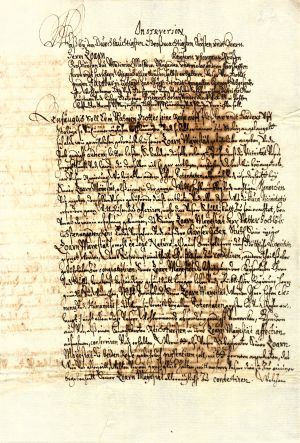

4. Supplementary instruction from Duke James to his envoy Georg Fircks. Mitau/Jelgava, 29 July 1646. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 676, pp. 35–36.

En route to France, Fircks was to carry out some other tasks for the duke. Among other things, James instructed his envoy to meet secretly with three Dutch privateers (state-supported pirates) in order to hire them to attack Spanish ships, including those of the Silver Fleet, i.e. ships transporting riches from the New World to Spain. The crews were to give an oath of loyalty to the duke, and the plunder was to be divided between the duke and the pirates in accordance with the custom of the Dutch privateers.

Such an operation was to be carried out in response to the seizure in 1645 of one of the duke’s ships at Dunkirk by Spanish privateers. James sought unsuccessfully to secure the return of the ship. Fircks did not undertake this task, because the international situation changed: peace talks began between Spain and the States General. In the years after that, James sought to obtain compensation from the King of Spain for the loss of the ship and cargo, adding interest each year, as a result of which, starting from the 1670s, he demanded the island of Trinidad, belonging to Spain, in compensation.

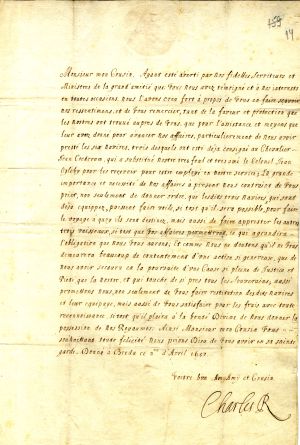

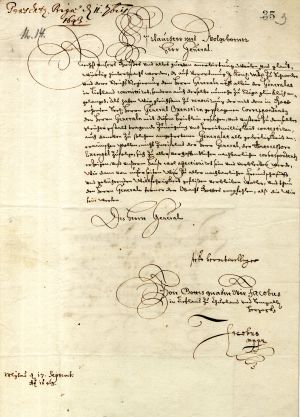

5. Letter from Charles II of England to Duke James. Breda, 2 April 1650 [old style]. In French. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 384, p. 14.

In this letter, Charles II, the son of the executed Charles I (Stuart), king of England and Scotland, thanks the duke for his long-continued support of the Royalists. Referring to an agreement on the supply of six ships, three of which have already been received by the king’s representative Sir John Cochrane, the king asks for a further three ships to be fitted out. He promises to return the ships and compensate the duke for all his expenses.

A large part of the aid prepared by James never actually reached the king’s supporters; however, already at the beginning of the 1650s he asked for a compensation of almost 376 thousand thalers from the English. This sum also included an annual pension of 400 pounds that the English had promised his father Duke of Courland William, because already in 1638 William had transferred the right to this payment to his son.

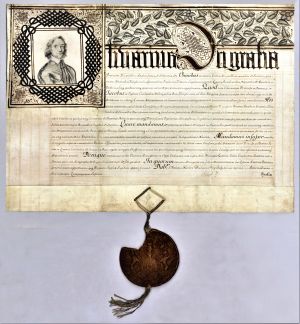

6. Trading and shipping agreement between Duke James and the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell. Westminster, 17 July 1657 [old style]. Original on parchment, with the Great Seal of the Republic of England attached. LVVA, collection 5561, inventory 2, file 158.

The agreement was drafted in the form of a privilege or concession. It gave the duke’s ships and people freedom of shipping and trade in England and in all of its colonies and dominions, on land and at sea. All officials of the republic were ordered to consider the duke’s people as friends and provide them with the necessary assistance.

Even though Duke James had supported the Stuarts in the English Civil War, it was more important for him to promote the realization of his trading and colonial aims. Accordingly, in 1654, after the Parliamentarians had gained the upper hand in England, the duke concluded a neutrality agreement with Oliver Cromwell, followed by a free navigation agreement in 1657. It did not prove very significant, because during the time the duke was in Swedish captivity the monarchy was restored in England.

7. Instruction from the duke to his envoy in Russia, Friedrich Johann von der Recke. Mitau/Jelgava, 20 February 1646. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 2, file 2942, pp. 23–24.

When James sent Recke, Supreme Captain of Selburg/Sēlpils district, to the Russian Tsar, he gave him a detailed instruction listing the tasks he was to undertake in Russia. Recke was to convince Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich to buy back two jewels from the Tsar’s crown that had come into the hands of the duke’s father during what is known as the Time of Troubles (Smuta). He was also to make an offer from the duke of raising a few thousand mercenaries for fighting the Tartars, if the Tsar could obtain permission from the King of Poland, and to find a bride for the young Alexei in Europe. For his part, James wished to ask the Tsar to grant him free trading rights in Russia and permit his representatives to travel to Persia unhindered. Apart from this, Recke had to purchase the duke some good Persian horses as well as three or four camels, which could then be used to convey the envoy’s baggage to Courland, and hire a Russian interpreter to work at the duke’s court. There were a string of further requests from the duke.

Wishing to develop his trading connections eastwards as well, James strove to make use of the ascent to the throne of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich (1629–1676) in 1645 to establish diplomatic relations.

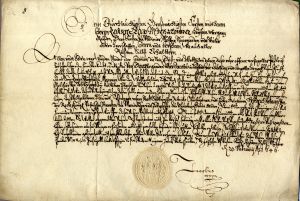

8. Passport issued by Duke James to Friedrich Johann von der Recke, the envoy to Russia. Jelgava, 20 February 1646. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 2, file 2942, p. 28.

In this travel document or passport (Passbrief), Duke James requests that his envoy be permitted to travel freely in the Tsar’s state and be given the necessary assistance and support during his travels.

Recke did not, however, manage to cross the border into Russia, because the Tsar’s court prohibited him entry, declaring that, since the duke’s predecessors had not sent envoys to the Tsars, James’s envoy could not be received either.

9. Letter from Alexei Mikhailovich, Tsar of Russia, to Duke James. Moscow, 11 May 7162 [21 May 1654]. LVVA, collection 7363, inventory 3, file 221.

The war begun by Russia in 1654 against Poland-Lithuania marked a new beginning in Russian–Courlander relations. Shortly before going on the march, Alexei Mikhailovich sent envoys to the Elector of Brandenburg and the Duke of Courland announcing that he was making war on Poland. In the introduction to the letter, the Tsar recalls the unsuccessful embassy of 1646, but now expresses his readiness to receive James’s envoys. The main body of the letter deals with the reasons that had prompted the Tsar to go to war against Poland-Lithuania, and Duke James was urged not to provide Poland with military, financial or other assistance.

The letter shows that the Tsar was not well informed about the Duke of Courland’s military capability or his obligations towards the King of Poland as his overlord. Accordingly, the Tsar had decided to take steps in advance to avert the duchy’s potential involvement in the war against Russia. Under the terms of his investiture, James had to provide the king with a vassal army, should there be fighting in Courland, or a certain sum of money, if the fighting were to take place outside of the duchy. Thus, to provide assistance was his duty. Thereforce, James was reticent in his reply to the Tsar. The duke expressed his gratitude for the opportunity to send an envoy to Russia, but with regard to the war, he only expressed his regret at the strife between the two sovereigns and offered his services as an intermediary to defuse the clash. Since James did not wish to become embroiled in the conflict, for additional security in late 1654 he sent his advisor Georg Kühnradt to the King of Poland, asking for Courland to be permitted to remain neutral in the Polish–Russian War. The king agreed to this request on 17 January 1655 (see the document in the section on the war).

Most importantly, however, this letter marks the beginning of James’s diplomatic relations with Russia.

10. Letter from Afanasy Ordin-Nashchokin, Voivode of Tsarevich-Dmitry-Grad (Koknese), to Duke James. Tsarevich-Dmitry-Grad, 2 February 7165 [12 February 1657]. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 747, p. 12.

In October 1656, the Russian diplomat and military leader Afanasy Ordin-Nashchokin became governor of the territories of Swedish Livonia that had been taken by the Russians. His residence was at Kokenhusen/Koknese, which the Russians renamed Tsarevich-Dmitry-Grad. While in this post, until 1661, Ordin-Nashchokin maintained active contacts with Duke James. The two sides exchanged the latest political information and cooperated on issues of everyday life, as attested by this particular letter. Ordin-Nashchokin complains about the peasants of Linde estate, who had robbed several Russian merchants’ boats on the River Düna/Daugava, and also asks the duke to sell him a consignment of rye.

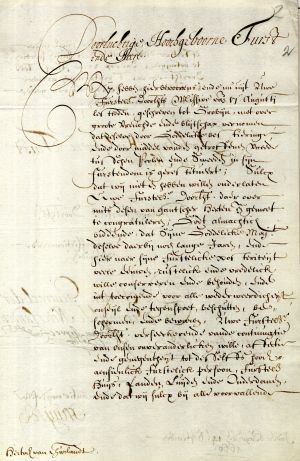

11. Letter from Duke James to Hermann Wrangel, Swedish Governor-General of Livonia. Mitau/Jelgava, 17 September 1643. LVVA, collection 7363, inventory 1, file 647, p. 3.

In his letter, James congratulates the new governor-general Hermann Wrangel on his arrival in Riga and expresses the hope that Wrangel will continue the neighbourly relations existing in the time of his predecessor Bengt Oxenstierna.

The date of receipt, 11 September 1643, is noted at the upper left corner of the letter. The difference in dates results from the different calendars in use: the Swedes were using the Julian calendar, or old style, while the Duchy of Courland was using the Gregorian calendar, or new style.

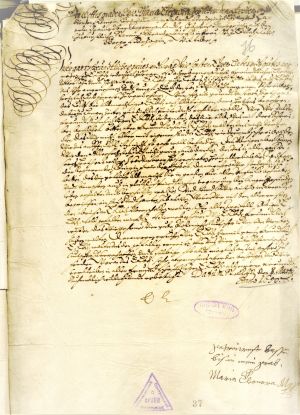

12. Letter from Maria Eleonora, Dowager Queen of Sweden, to Duke James. Stockholm, 8 March 1650 [old style]. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 641, p. 76.

The queen announces that she has begun building a new castle with a garden, promising she would soon send the duke the design, which he was sure to appreciate. For her part, the queen asked the duke to send her four good Polish coachmen, whom she wished to take into her service.

The ducal house of Courland had a long-standing friendship with Maria Eleonora (1599–1655), widow of Gustav II Adolf of Sweden (1594–1632); moreover, she was a maternal cousin of Duke James.

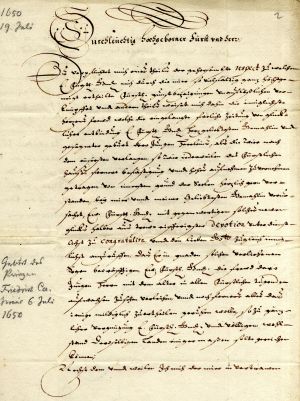

13. Letter from Magnus Gabriel De la Gardie, Swedish privy councillor and Governor-General of Livonia, to Duke James. Stockholm, 19 July 1650 [old style]. LVVA, collection 7363, inventory 3, file 953, p. 2.

In reply to a letter from the duke, De la Gardie congratulates James on the birth of a son [Frederick Casimir] and expresses his goodwill towards the duke. He also declares that he will pass on the duke’s offer to the queen.

At this time, Duke James was actively engaged in organizing peace talks between Poland-Lithuania and Sweden, and his offer evidently related to this question.

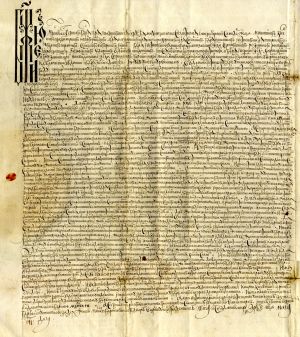

14. Letter to Duke James signed by Doge Francesco Molino and his secretary Christofforo Suriano. Venice, 24 May 1647. Original on parchment in Italian, with the personal lead seal of the Doge attached. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 728, p. 21.

In organizing peace talks between Poland-Lithuania and Sweden, Duke James turned to the Republic of Venice with the request that it become one of the mediators. The duke chose the Courland noble Nicolaus von Korff, serving as a colonel in Venice at the time, to forward this request. In the letter of credence issued to Korff, written in Latin, James uses the term Internuntius, which the Venetians refused to recognize as conferring diplomatic status. In spite of the explication that this term referred to an “envoy extraordinary”, Korff was not granted an audience at the Doge’s palace. However, in reply to a written submission from the envoy, the Venetians did agree to mediate in the peace talks, as they informed the duke in a letter.

Under the 1635 Treaty of Stuhmsdorf, the Elector of Brandenburg and the Duke of Courland were entrusted with the task of turning the truce between Poland-Lithuania and Sweden into a permanent peace. Accordingly, Duke James, who very much desired to prevent a new war close to the borders of Courland, began organizing peace negotiations already in the first years of his rule. As a result of his efforts, a peace congress convened in summer 1651 in Lübeck. It continued with interruptions until March 1653 but came to nothing in the end.

15. Letter from Reinhold Derschaw, representative of Brandenburg at the congress in Lübeck, to Duke James. Lübeck, 3/13 March 1653. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 376, p. 120.

In his letter, the envoy of the Elector of Brandenburg expresses his regret at the failure of the talks, because, in spite of the efforts of all the intermediaries, including the duke, no agreement could be reached. He further writes that he is sorry the negotiations had not touched on the duke’s demands, namely his claims against Sweden relating to the territories of the duchy that Sweden had invaded in the 1620s and which the Swedes had retained after the war.

Brandenburg’s representatives Derschaw and Hoverbeck had arrived at the congress when it was already nearing its close. The duke’s envoys – Chancellor Melchior von Folckersamb and advisor Johann Wildemann – had made a much greater contribution to the work of the congress. Pierre Chanut, the envoy of the King of France to Sweden and the main intermediary at Lübeck, was also very instrumental in getting the Polish and Swedish delegations to actually begin their negotiations.

16. Letter from Ernst, Duke of Saxony, to Duke James. Friedenstein Palace, 11 April 1651. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 641, p. 147.

Duke Ernst of Saxe-Gotha (1601–1675) writes to Duke James that he has long wished to become acquainted with him. Now he has learned that James knows of a technology of making plaster decor appear as if made from jasper asks for a description, so that he may apply this technique in construction work on his palace.

17. Congratulation to Duke James from the States General. The Hague, 14 September 1660. In Dutch. LVVA, collection 5759, inventory 2, file 1324, p. 2.

In reply to a letter from Duke James, sent from Grobin/Grobiņa on 17 August, the government of the United Provinces of the Netherlands, or States General, congratulates the duke on his release from captivity and return to Courland.

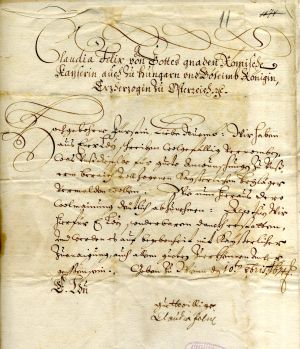

18. Letter from Claudia Felix, Holy Roman Empress of the German Nation, to Duchess Louise Charlotte. Vienna, 10 October 1674. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 257, p. 11.

Claudia Felicitas or Claudia Felix (1653–1676) thanks Louise Charlotte for her good wishes on the occasion of the marriage of Claudia, Archduchess of Austria, to Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor, in October 1673.

Duchess Louise Charlotte’s correspondence was just as extensive as that of Duke James himself.

19. Instruction from Louis XIV of France to the Duke of Beaufort. Fontainebleau, 13 June 1666. Transcript authenticated by Johann Tobias Tregelius, secretary to the Duke of Courland. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 641, p. 163.

The King of France instructs François de Bourbon-Vendôme, Duke of Beaufort, who was general-intendent of French trade and the fleet, to make known to all French officers, ships’ captains and port officials that the vessels of the Duke of Courland are permitted to sail freely in French waters and visit French harbours.

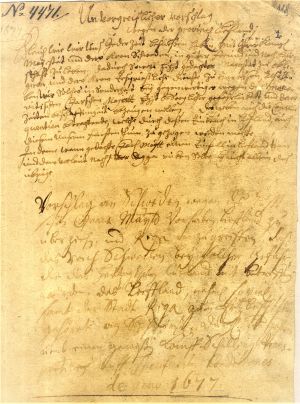

20. Letter from Alexis-François Dauvet, Marquis Desmarets, the French superintendent of falconry birds, to Duke James. Paris, 3 December 1678. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 683, p. 7.

In his letter, Marquis Desmarets (1615–1688) confirms that the 18 falconry birds James had sent as a gift to Louis XIV of France had been received.

Starting from 1677, James strove to re-establish the right he had been granted in 1666 of free navigation and trade in the ports belonging to France, in addition to which he requested the restitution of four of his ships and their cargoes that had been seized by French corsairs starting from 1670, or for their value to be compensated. In compensation, the duke wished to receive a piece of land, such as the island of Martinique in the Caribbean. The duke sent falconry birds to France on several more occasions, but all of his efforts in the matter of compensation turned out to be in vain.

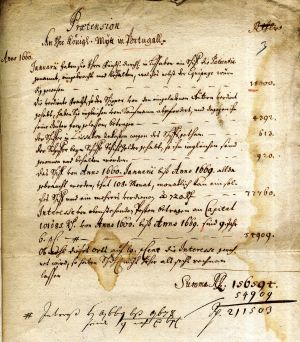

21. Calculation of Duke James’s claims against Portugal. 1669. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 725, p. 3.

The duke lists his losses following the seizure of his ship Patientia (“Patience”) in Lisbon in January 1660. According to James’s calculations, the ship and its crew were worth 18,000 thalers, and the freight was worth 4392 thalers; the expenses incurred by the captain and the crew in Lisbon came to 1533 thalers. Moreover, the Portuguese had made use of the ship all of these years, which could potentially have brought them 77,760 thalers. Accordingly, the losses in nine years came to 101,685 thalers. The duke added 6% interest to this sum, even though the usual interest rate in Portugal was apparently 10%, and over nine years this had amounted toto 54,909 thalers. The total losses by 1669 were calculated as 156,594 thalers. A calculation of interest for another nine years is added at the bottom, and accordingly the duke’s claim reached 211,503 thalers.

This document demonstrates the way in which James calculated his foreign debts. The duke never recovered most of them in the course of his lifetime, bequeathing them to his son Frederick Casimir. Interestingly, in his will of 1673, James mentions only 45,000 as the debt owed by Portugal. Unfortunately, the documents provide no information concerning the duke’s relations with Portugal during the second half of his rule.

22. Letter from Christian V of Denmark to Duke James. Smidstrup in Halland, 22 September 1676. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 733, p. 1.

In reply to the announcement of the death of Duchess Louise Charlotte, sent by the duke on 26 August, the King of Denmark expresses his deepest sympathy to the duke.

Christian V of Denmark (1646–1699) was married since 1667 to Charlotte Amalie (1650–1714), niece of Louise Charlotte, Duchess of Courland.

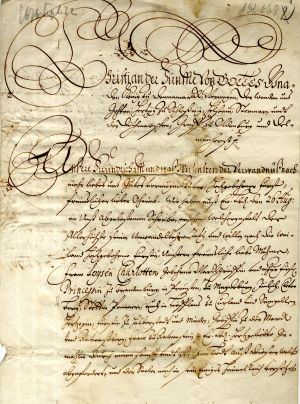

23. Proposal from Duke James to purchase Livonia from Sweden. 10 December 1677. Draft. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 384, p. 118.

In 1677 the rumour had spread that the Russian Tsar was once again preparing to invade Swedish Livonia. Accordingly, Duke James addressed a proposal to the Swedes, offering to purchase Livonia and Riga for 10% of the province’s annual revenue, deducting the sum of the debt that the duke was demanding from Sweden. For his part, James promised to uphold all the privileges enjoyed by the inhabitants of Livonia and obtain a promise from the Tsar not to invade.

Duke James hoped to exploit the situation in which Sweden found itself at the time: the Swedes were already at war with Brandenburg-Prussia and Denmark. Involvement in a war with Russia as well could be extremely dangerous for Sweden. However, the rumours proved untrue, and Riga and Livonia were too important to the Swedes for them to agree to the duke’s proposal.