In the time of Duke James, the economic activities of the duke formed the basis of the country’s economy, since the income they generated not only provided for the duke himself and his family but also maintained the state apparatus. The nobility was economically privileged and essentially independent, while the duke sometimes viewed the merchants of the towns not only as partners but also as competitors.

Most of the income came from the duke’s estates. These provided the goods exported to Europe as well as actual monetary income. The development of the duke’s fleet was motivated by James’s wish for extensive trading contacts, while the establishment of various crafts workshops and manufactories was, first and foremost, intended to satisfy the duke’s economic needs. The question of the profitability of the duke’s economy is still unresolved.

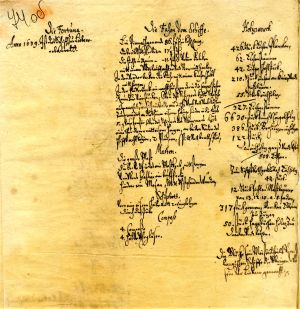

1. Inventories of the first ships built on the order of Duke James. 1639, 1640. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 849, pp. 72, 74.

It has been asserted in the literature until now that James built his first ships in Goldingen/Kuldīga. However, the sources do not confirm this. The inventories of ships recently discovered in the document collections of the Dukes of Courland indicate that the first two ships in Duke James’s fleet were built in Libau/Liepāja: the pinnace Fortuna in 1639 and the ship St. Jacob in 1639/1640. However, already in the second half of the 1640s the shipyard was transferred from Libau/Liepāja to Windau/Ventspils. The reasons for this have still not been properly established.

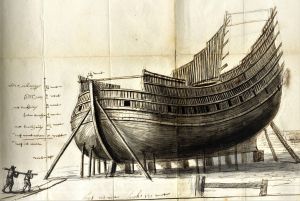

2. The process of building ships. Drawing by Johann Streck. First half of 17th century. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 850d, pp. 6, 7.

During the rule of Duke James, almost a hundred ships were built in Windau/Ventspils and Libau/Liepāja. Most of these were small sailing ships: fluyts, frigates, yachts, galiots, pinnaces, etc., which had to have a small draught because the waters of the Baltic Sea are shallow. However, this did not prevent the duke’s ships from making distant voyages as well, to the coasts of Africa and America. Duke James operated 20–25 ships at any one time, reaching a maximum of 35 in certain years.

Duke James’s main shipyard was located in Windau/Ventspils. However, in 1677, Prince Frederick Casimir re-commenced the building of ships for the duke in Libau/Liepāja as well. Seagoing vessels were not built in Goldingen/Kuldīga, because the River Windau/Venta was too shallow.

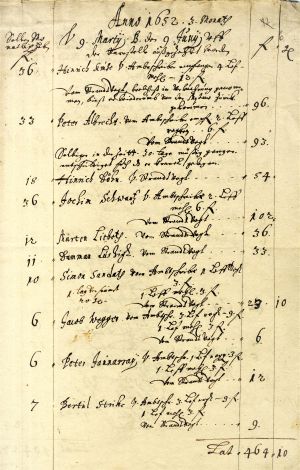

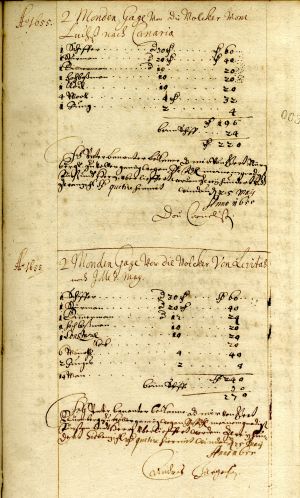

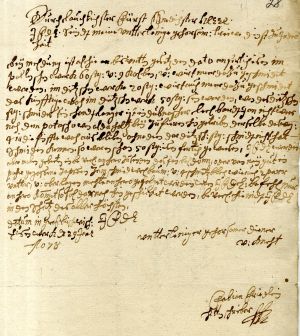

3. Wage lists of craftsmen employed at Windau/Ventspils shipyard. June 1652. Excerpt. LVVA, collection 6999, inventory 44, file 1126, pp. 6, 9.

It was in the 1650s that Duke James’s fleet really developed and shipbuilding flourished. The master shipbuilders came from Lübeck, Kolberg (present-day Kołobrzeg), Sweden and Holland, and a large number of Latvians were also employed in various capacities. In 1652, the duke enlarged the Windau/Ventspils shipyard: in April he hired another 21 Dutch ship carpenters in Amsterdam, led by master shipbuilder Gert Johansen (also Gerrit Janssen). The lists give the names of the ship carpenters, their monthly pay and the actual amount they had received for the second quarter of 1652.

The duke made Gert Johansen the senior shipbuilder, and on 25 September issued an instruction that all the other artisans of the shipyard should obey Johansen, authorizing him to dismiss anyone who did not comply. The duke also ordered that for every day that a worker was absent without reason, two days’ pay should be deducted from his remuneration.

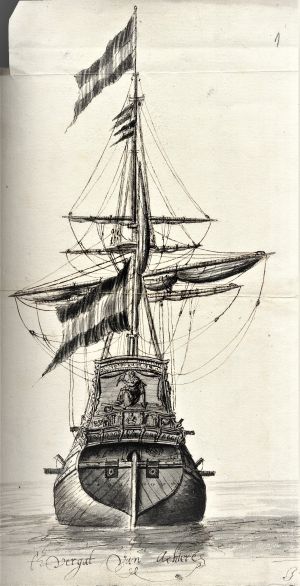

4. Sailing ships in the time of Duke James: a frigate and a yacht. Drawings by Johann Streck. First half of 17th century. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 850d.

Duke James’s fleet did not include men-of-war, because the Dukes of Courland had been following a policy of neutrality already since the 1620s. Accordingly, we cannot speak of a Courland’s navy. All of the duke’s ships were merchantmen and fishing vessels, and the armaments placed on them were intended only for defence. But they were of little use, and a large proportion of the duke’s fleet ended up in the hands of pirates and privateers from various countries.

The loss of each ship was a great disappointment for Duke James, and he engaged in shipbuilding without calculating whether the ships paid for themselves. Sometimes, even the duke’s own people made so bold as to point this out, such as Henry Momber, his trading agent or factor in Amsterdam, who wrote in a letter to James on 17 February 1657 that the duke already had an unnecessarily great number of large vessels, and new ones were being built every day (Ihre Fürstliche Gnade haben doch alzuviel grosse Schiffe, die nicht noetig seint, undt noch taglichs neue gebaut.). And Sophie Hedwig, Landgravine of Hesse, wrote in a letter to her sister, Duchess Louise Charlotte, on 28 July 1670 that, if the duke were to build a couple of ships fewer, then he would have the money for his daughters’ dowries (Wan Ewer herr 2 schiff ungebaut liß, so hetten ihr gnaden vor 2 töchter das heurahtsgelt...).

5. List of seamen’s wages. Windau/Ventspils, 22 May 1655. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 837, p. 34.

The captains of the duke’s ships and the leaders of his expeditions were for the most part foreigners, and accordingly the majority of sailors and soldiers were likewise recruited abroad – mainly in Denmark, Germany, Holland and Britain. Some of them also settled in the duchy. The tales according to which large numbers of Latvians served on the duke’s ships are quite unfounded. There were very few Latvians serving on the duke’s ships – Latvian sailors were the exception rather than the rule.

In this document, Dou Cornelissen, captain of the ship Luchs (Lynx), states that he has received 220 thalers as two-months’ pay for a crew of 10 for a voyage to the Canary Islands. Andreas Jurgensen, captain of the ship Levitas (Lightness), had received 270 thalers as two months’ pay for a crew of 14 for a voyage to the island of Maio in Cape Verde.

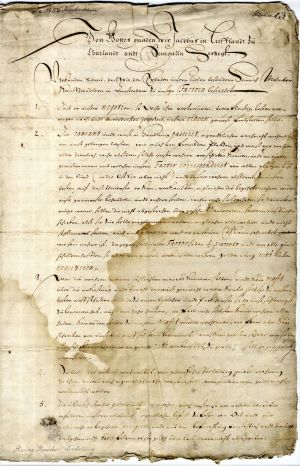

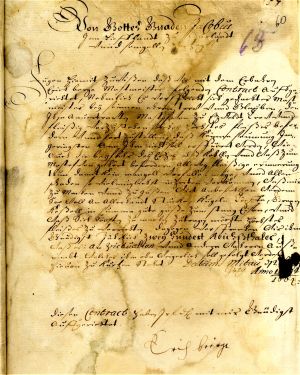

6. Agreement between Duke James and the Amsterdam merchant Henry Momber. Amsterdam, 1 June 1650. LVVA, collection 7363, inventory 3, file 439, pp. 3, 4.

In accordance with the agreement, Momber became the duke’s commercial agent or factor, who was to organize trade in the duke’s goods outside of the Baltic Sea and manage his ships, sending weekly reports to James. For his work, Momber was to receive 4% of the value of the goods sold.

Henry Momber was one of a number of commercial agents collaborating with Duke James. The duke also had factors in Danzig, Torun, Lübeck, Hamburg, Oldenburg, Copenhagen, London, Newcastle, Bordeaux and elsewhere. He collaborated with some of them for many years, whereas he was engaged in protracted legal disputes with other agents over financial matters.

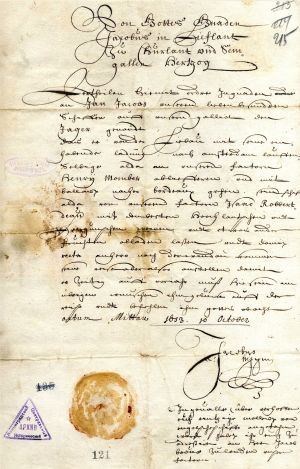

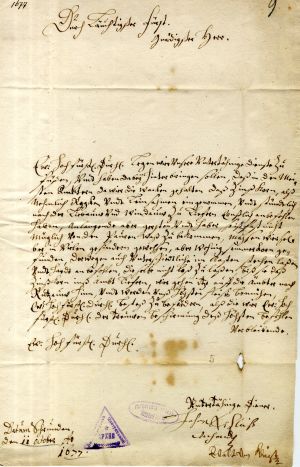

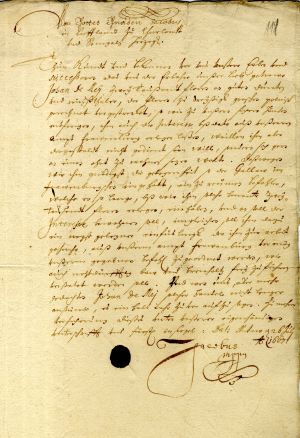

7. Instruction from Duke James to ship’s captain Jan Jacobs. Mitau/Jelgava, 10 October 1653. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 709, p. 215.

James ordered Jacobs to sail the galiot Jager (Hunter) from Libau/Liepāja to Amsterdam, where he was to turn over the cargo to the duke’s factor Henry Momber. From there, he was to sail with ballast to Bordeaux in France, call on the duke’s agent Isaac Robbertdeau and take on wine and other goods. James ordered that this cargo be brought directly to Windau/Ventspils. The voyage had to be planned so as to arrive in Windau/ Ventspils in the spring of the following year.

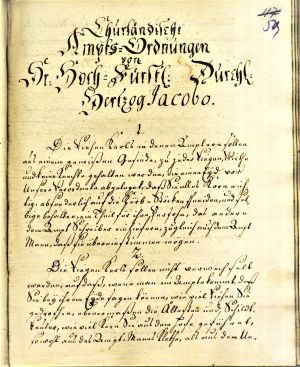

8. Duke James’s administrative code (Amts-Ordnung) for the estates. 1663. Transcript. First page. LVVA, collection 5759, inventory 2, file 692, p. 59.

So as to restore the administration of the estates after the ravages of the Polish–Swedish War (1655–1660), Duke James issued a special code for his estate managers. This was based on the codes established in 1636 and 1649 and consisted of 125 articles. Certain of the articles provide a reflection of the realities of that particular time. For example, article 64 prohibited Germans from living in peasant homesteads without the duke’s permission; instead, they were to move to the towns, so that these might develop. In article 71, the duke stipulates that estate managers are not to return peasant fugitives to their previous owners without the duke’s agreement, even though this contradicted a decision of the diet.

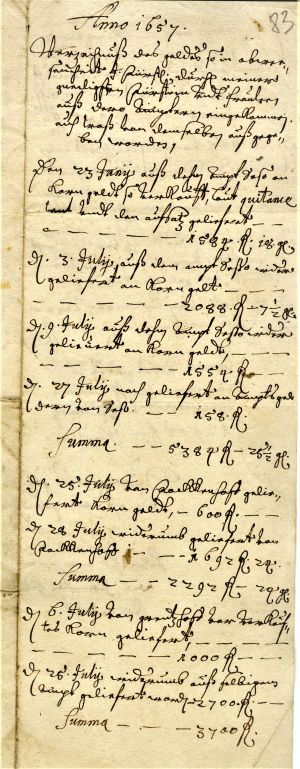

9. Notes on the finances of the duchess. 1657. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 1456, p. 83.

In this document, Louise Charlotte’s accountant sets out the incomes received in summer 1657 from her estates of Sessau/Sesava, Fockenhof/Bukaiši, Grenzhof/Mežmuiža, Kuckern/ Ukri and Friedrichshof/Lipsti. The money came mainly from the sale of grain and malt. A total of 12,905 florins 19½ groats had been received. In accordance with an instruction from Louise Charlotte, 3000 florins had been handed over to the duke, and small sums had been paid out to cover various minor necessities, such as soap. An unnamed goldsmith had received 60 florins for making a pair of earrings for the duchess.

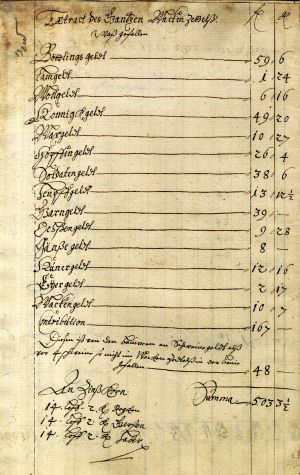

10. List summarizing peasant dues on the estate of Friedrichshof/Lipsti. 1673–1674. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 1456, p. 132.

The peasants on the duke’s estates paid dues in kind as well as in money, the proportions of these varying from one estate to another. In the case of Friedrichshof/Lipsti, the only dues collected in kind were rye, barley and oats – a total of 14 bushel or Lof (c. 48 kg) and two pecks of each, whereas the dues in the form of bullocks, rams, lambs, chickens, eggs, geese, hops, wax, wool, woollen yarn and hemp were replaced by monetary payments. Apart from this, the peasants also had to pay some money and contributions, which were collected on the basis of decisions passed by the diet, depending on specific needs. The size of the payments and dues was not unified; instead, it was dependent on the size of each homestead, its prosperity and the form of economic activity.

11. Report to the duke by Johann Nikolaus Wiegandt, Captain of Schrunden/Skrunda Castle, and stable master Ewald von Kleist. Schrunden/Skrunda, 11 October 1677. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 368, p. 9.

The officials report that they would soon be sending to Libau/Liepāja and Windau/Ventspils the rye and linseed so far collected from the peasants. On the other hand, barley and oats were hard to obtain from the peasants, even though they themselves had inspected peasant farmsteads and had imprisoned some peasants pending payment of the dues. The officials planned to proceed to Rutzau/Rucava.

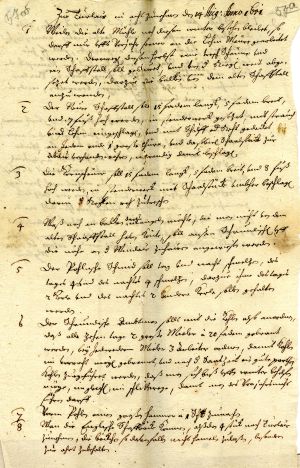

12. Instruction from Duke James to the manager of Turlau/Turlava estate. 14 August 1651. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 437, p. 57a.

Among other things, the duke orders a shed to be provided in autumn for threshing grain (Dresch-Scheune) as well as a new barn for sheep, which was to be a timber-frame structure with a reed roof and a large gate at each end. The building timbers were to be taken from the old barn and, if necessary, timber should be cut in the forest on the bank of the Windau/Venta river. Once the English rams (englische Schafbocke) had been brought, four of them were to be kept at Turlau/Turlava, while the manager of the sheep flock (Schaeffer) was to take the rest to Candau/Kandava and Neuwacke/Jaunpagasts and establish sheep farms there.

Sheep were also kept on other ducal estates, such as Rutzau/Rucava. It should be noted that sheep were used to provide not only wool but also meat, which the duke’s court generally consumed in larger quantities than the majority of European courts.

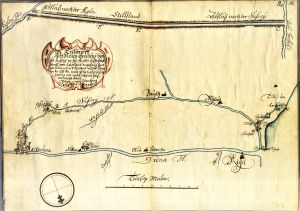

13. Canal system planned by Duke James. Johann Svenburg. 1668. LVVA, collection 673, inventory 1, file 979, pp. 11, 12.

In the 1660s, Duke James decided to undertake canal-digging in order to create new waterways for transporting goods to the coast, thus circumventing Riga, which was the duke’s main competitor for trade and was, moreover, reaping the benefit of customs duties imposed on goods from Courland. In 1667, work commenced on a project to straighten and deepen the River Eglone/Eglaine and dig a canal that was to connect the Eglone/Eglaine with the Wilkup/Vilkupe (shown as Sussey/Susēja on the map). A canal was also envisaged that would connect Lake Kanjer/Kaņieris with the sea, and a passage for boats was to be built through the mill dam at Schlock/Sloka. After the Rigans heard of the work that was underway, they sent engineers Franciscus Murrer and Joachim Hardeloff as spies to the Selonia/Sēlija region in October 1667. They reported on the progress of the work and the interest shown in the new waterways by Lithuanian merchants in the border area. The following spring, engineer Johann Svenburg travelled to Courland from Riga. Alarmed at the duke’s plans, Riga town council complained to the King of Sweden. Under pressure from Sweden, in 1668 James ordered that canal-digging work be halted. At the same time, the duke himself accepted that the ambitious plans were technically impossible to realize.

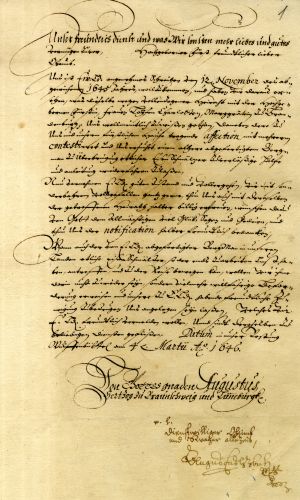

14. Letter from Augustus, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg to Duke James. Wolfenbüttel, 4 March 1646. The date of receipt, 27 April 1646, appears on the envelope. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 1693, p. 1.

In reply to a letter from Duke James of 12 November 1646, Duke August (1579–1666) congratulates James on his marriage to Louise Charlotte, Princess of Brandenburg. He also grants permission for James to hire some iron-smelters in his lands, so that they might work in Courland.

15. Report to the duke from Fabian Friedlein, manager of Grossbuschhof/Birži manufactory. Grossbuschhof/Birži, 29 January 1678. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 1694, p. 28.

Friedlein reports that the Polish smiths had so far produced 60 bars in their forge, while the German craftsmen had produced 20 in their forge, although by the following week 50 bars would probably already have been made. According to the report, the work of the German smiths was delayed because their helper from Dubena/Dignāja, Lielbāržu Jānis (Leelbardt Jan), had been assigned to other work.

The ironworks at Grossbuschhof/Birži had been established together with a glassworks in 1652. It was located on the Nord-Sussey/Ziemeļsusēja river, not far from village Slaboda (since 1670 town of Jacobstadt/Jēkabpils) and is marked on the map by Johan Svenburg as Eysen Hammer. By the 1670s, the ironworks equipment was already dilapidated, and the works were being managed inefficiently. As a consequence, output was very low.

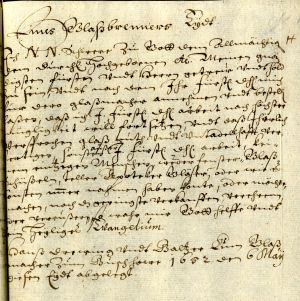

16. Text of the oath of a master glassworker. Mid-17th century. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 2300, p. 104.

On taking up his work, the artisan swore to be loyal and diligent, to work only for the duke and not to trade in the window glass, apothecaries’ vessels, bowls and other kinds of wares being produced. Below the text is a note stating that this oath had been given on 6 May 1652 by the craftsmen of the Grossbuschhof/Birži glassworks Hans Drewing and Balzer Kum.

The two craftsmen were employed at Grossbuschhof/Birži for 25 years. In the time of Duke James, glass was also being produced on the estates of Roennen/Renda and Baldon/Baldone.

17. List of items produced at Baldon/Baldone ironworks. 1677. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 1694, p. 19.

The following iron castings are listed as having been produced during the operation of the blast furnace, from 28 September to 24 November 1677: 12 eight-pound cannons, 13 six-pound cannons, two small howitzers, one large grapeshot cannon, two large mortars, 209 hand grenades, 230 cannonballs of different calibres, half a barrel of pistol shot, wheels for gun carriages in Bauske/Bauska Castle, one large smith’s anvil, seven large vodka cauldrons, 25 smaller cauldrons as well as various-sized pots with and without lids, crucibles, mortars, metal sheets, fire grates, etc.

The Baldon/Baldone ironworks, established in the 1650s, consisted of several workshops, located at Baldon/Baldone itself and at Neuhof/Vecmuiža (nowadays Vecumnieki) and Reschenhof/Rieži, and was the largest of Duke James’s ironworks. The craftsmen included Germans, Poles, Walloons, Swedes and Latvians.

Other works producing metal goods existed at this time on the estates of Grossbuschhof/Birži, Turlau/Turlava, Schrunden/Skrunda and Luttringen/Lutriņi, as well as in Mitau/Jelgava.

18. Agreement between Duke James and blast furnace master Claß De Ny. Mitau/Jelgava, 8 November 1679. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 2057, p. 151.

Claß De Ny was hired by the duke to work at the newly-established Angern/Engure ironworks, being promised an annual wage of 200 thalers. Apart from this, he was assigned two helpers to operate the blast furnace and four labourers to supply charcoal and ore.

The Angern/Engure works was the last of the ironworks established by Duke James, going into operation shortly before the duke’s death. The information, often given in the literature, that Duke James also built an ironworks at Eden/Ēdas, not far from Goldingen/Kuldīga, is erroneous: this works was established by his son, Duke Frederick Casimir.

19. Report by the duke’s inspector of workshops Claude Lafontaine on the work of craftsmen from 27 April to 3 May 1678. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 1848, pp. 18–19.

Lafontaine inspected various kinds of workshops scattered across in a large area – from Thomsdorf/Tome to Mesothen/Mežotne. At this time, barrels were being made on the estate of Thomsdorf/Tome; a rolling mill and a French cloth weaver was operating at Eckau/Iecava; in addition to ordinary cloth, items of taffeta and damask were being made at Mesothen/Mežotne; a fabric dyeworks and a wallpaper weaving workshop had been established at Annenburg/Emburga, also producing leather wallpaper; Annenburg/Emburga also had an amber-turner and a goldsmith, who mainly produced gold thread and gold leaf. Although these were not large workshops, they employed Latvians alongside foreign craftsmen.

The place-name Lafonteine in Baldon/Baldone municipality comes from the surname Lafontaine.

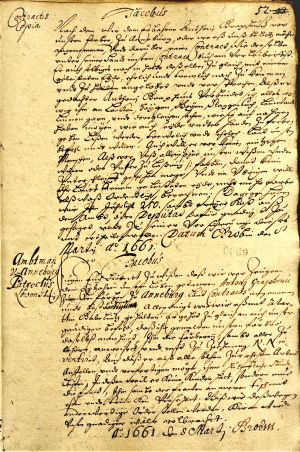

20. The duke’s agreement with fabric dyer Anthoni Grapheus and instruction to Patroclus Loewenstein, manager of Annenburg/Emburga. Grobin/Grobiņa, 8 March 1661. Copies. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 265, p. 69.

On his return from captivity, in the summer of 1660, Duke James immediately set about rebuilding the ravaged economy. Among other measures, he invited various craftsmen who had left during the war to return to Courland. Some did indeed return, such as ship’s carpenter Gert Johansen. Others declined, such as Martin Gabelintz, the Königsberg fabric dyer, who had previously worked at Annenburg/Emburga. In his place, a certain Anthoni Grapheus was hired in early 1661, employed to dye various kinds of fabric, including cloth for flags, linen and woollen thread, and other items. The contract also forbade him from working for anyone else without permission from the duke. He was to receive 250 florins a year in cash and free board or produce from the estate. The duke also instructed Loewenstein, the manager of Annenburg/Emburga estate, to make available to Grapheus the existing workshop and equipment. Since the craftsman had no children, James ordered that initially Grapheus and his wife should have their meals at the manager’s table.

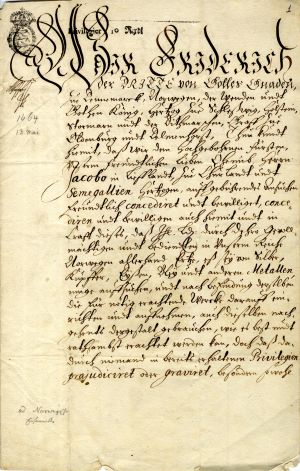

21. Privilege to Duke James granted by Frederick III of Denmark. Copenhagen, 13 May 1664. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 2, file 3146, p. 1.

At James’s request, the king granted the duke the right to prospect for various ores in Norway and operate metalworks in accordance with the Mining Regulations (Berg-Ordnungen) that were in force in Denmark, which also stipulated the dues he was to pay to the Danish state treasury for every hundredweight of iron produced.

It is not known whether James actually made use of the possibility of prospecting for new ore sources, but in the summer of that same year the mines and ironworks at Eidsvoll (Edswold) were handed over to the duke’s representatives. The duke also obtained the right to run the works at Julsrud and Vik (Wig). The duke sent Courlanders to Norway, including some Latvians, as well as workers hired elsewhere, for example in Poland-Lithuania. Most of the iron produced there was sold locally in Denmark-Norway, but the duke retained part of the output for his own needs. There is no evidence in the sources that ore was transported to Courland from Norway. Duke James’s rights to the ironworks were re-affirmed by royal privileges issued in 1669 and 1674.

22. Duke James’s contract with blast furnace master Erich Berg. Mitau/Jelgava, 2 July 1664. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 2057, p. 60.

In accordance with the terms of the contract, Berg was to take up work at the Eidsvoll ironworks and manage the operation of the blast furnace. The duke promised him an annual wage of 250 thalers.

There are very few preserved sources providing information about the duke’s enterprises in Norway, but the ones that do exist testify that they were, in general, unprofitable. This is also indicated by a letter from Duke James to Andreas Simonsen, his partner in Norway, on 6 November 1677, in which the duke expresses his surprise that the revenue from the ironworks is so small. He writes that he has sent people there one after the other, but that this has been of little use, because all they do is complain about one another. This applied, first and foremost, to the managers and clerks, but there was evidently also a high turnover of employees among the master craftsmen.

23. Announcement by Duke James. Mitau/Jelgava, 26 July 1667. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 1199, p. 111.

James declared that he had borrowed 2000 florins from Johann De Mey, where a florin was calculated as equivalent to 30 Polish groats. Since the lender did not wish to receive the interest due to him in money but asked that he be given a place to live instead, the duke granted him a plot of land and a house on the estate of Frauenburg/Saldus, along with one corvee labourer and free rights to cut firewood.

Just like the businessmen of today, Duke James was often short of cash, and in order to raise money, the duke was often forced to mortgage estates or other land, or borrow money, generally at an annual interest rate of 6–8 %.