In the time of Duke James, the court continued to serve as the main centre of administration and culture. The courtiers included the servants of the duke and his family, who always accompanied the ruler, as well as officials of various rank and court craftsmen, who would periodically visit the duke. Like other rulers of the age, Duke James attached great importance to his prestige, which meant increasing the number of courtiers and following the fashion trends of the time.

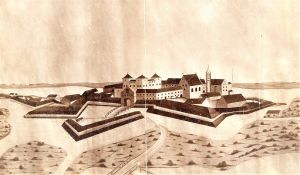

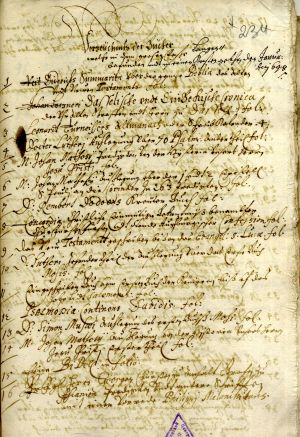

1. Mitau/Jelgava Castle in the mid 17th century. Drawing from the collections of the former Courland Provincial Museum. 19th century. LVVA, collection 640, inventory 2, file 262, p. 11.

In accordance with the Act of Composition of 29 November 1642, Mitau/Jelgava Castle officially became the duke’s main residence, which was subsequently further underlined by the transfer of the mortal remains of James’s mother, Duchess Sophie, from Goldingen/Kuldīga to Mitau/Jelgava in February 1643. However, the duke frequently also visited other castles and estates, especially at Goldingen/Kuldīga and Windau/Ventspils. After his return from Swedish captivity, starting from mid July 1660, the duke was forced to reside for more than a year at Grobin/Grobiņa Castle, which was at the time the war-ravaged duchy’s only castle in suitable condition to host the court.

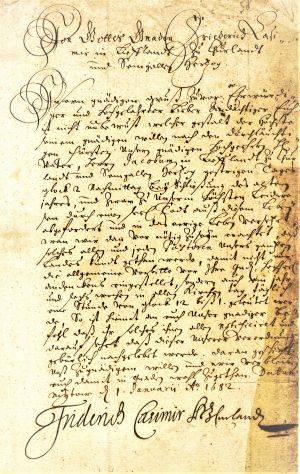

2. Letter from Duke James to Friedrich von Fürstenberg in Dünaburg/Daugavpils. Mitau/Jelgava, 9 August 1645. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 39, pp. 21, 22.

It was initially intended that the marriage of James and Louise Charlotte, Princess of Brandenburg, would be held in Goldingen/Kuldīga on 25 September 1645. The guests were to include the family of the Elector of Brandenburg as well as the Dowager Queen of Sweden Maria Eleonora (1599–1655), who was James’s maternal cousin, possibly accompanied by her daughter, Queen Christina of Sweden (1626–1689), and other prominent figures. The duke wished to hold a fittingly splendid welcome for the guests, and so the nobles of the duchy, including Fürstenberg and his sons and other adult relatives, were invited to come to Goldingen/Kuldīga either in carriages drawn by a team of six horses or on good riding horses, previously informing the supreme captain of Goldingen/Kuldīga district about the number of people, carriages and horses they would be bringing.

However, these plans changed soon, because Königsberg in Prussia was easier for the royal guests to reach and was deemed a more suitable venue for the festivities. In early October, James went to Prussia with an entourage of three hundred peoples, also bringing with him specially trained horses, which were to perform an “equestrian ballet”.

The wedding celebrations in Königsberg began on 9 October and lasted 11 days. In early November, the newlyweds arrived in Goldingen/Kuldīga. Here they spent several weeks, during which time they held celebrations for the people of the duchy, and on 8 January 1646 they arrived in Mitau/Jelgava.

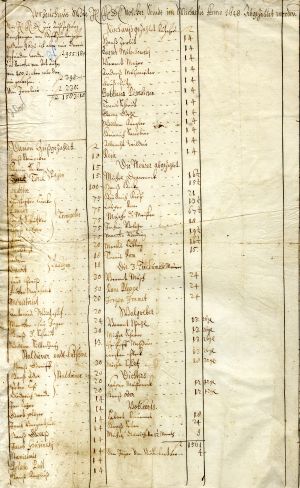

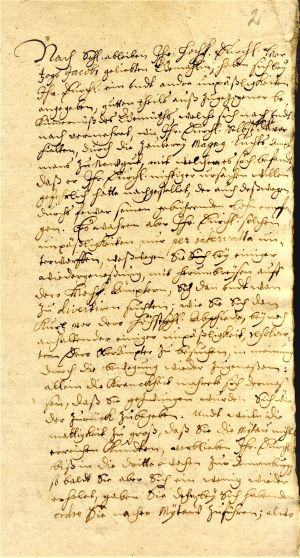

3. List of wages paid to members of the duke’s court. 1648. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 45, pp. 20, 21.

The list indicates which servants who had been paid at Michaelmas 1648 and which still had to be paid. In some cases, only the names are given, without indicating their occupation, while other individuals are referred to only by their profession: musicians, master of the mint (Münzmeister), sculptor, the young gardener, etc. It is apparent from the names that, in accordance with tradition, court hunters, kitchen and stable servants and coachmen included not only Germans and Poles but also a large number of Latvians – such as the cook Juris Saldenieks, stable boy Paulis from the Couronian free farmers ķoniņi, coachman Klāvs Pūce, huntsman Mārtiņš Kursis and others. Also mentioned are several Latvian masons and earthworks builders (Wallgreber). However, the table only shows only some of the people belonging to the court. Unfortunately, a full list of the residents of the court in the time of Duke James has not been found.

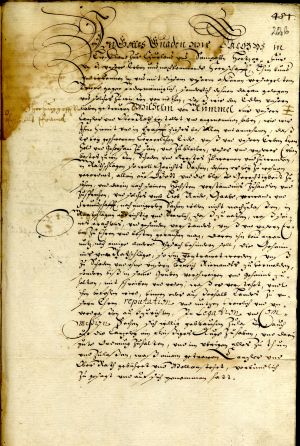

4. Instruction from Duchess Louise Charlotte to the Mistress of the Court (Hofmeisterin). Mitau/Jelgava, 14 June 1652. With the signature and seal of the duchess. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 368, pp. 1–3.

Along with James’s marriage, the number of courtiers increased, and this applies in particular to the female side of the court. Louise Charlotte had her own circle of servants, who performed their everyday tasks in accordance with the rules she had laid down. These rules were instituted along with the appointment of an unnamed lady of the duchess’s court as Hofmeisterin or mistress of the court. She had arrived from Prussia together with Louise Charlotte. The noble ladies and mademoiselles of the court were subordinated to the Hofmeisterin, as were servants of the lower ranks. In the introduction to the document, the duchess reminds her that ancient custom and tradition is to be followed in all things; in particular, she was to see to it that every lady at court strictly observed the morning and evening prayers. The young ladies had to engage in handicrafts during the daytime, and were not to leave the room where they were working without permission. She was also to see that the maidservants rose at half past five in winter and at five in summer, and did not show any laxity in their coiffure or dress.

5. Order by Duke James on the appointment of Reinhold von der Osten, called Sacken, as Court-Marshal (Hofmarschall). Mitau/Jelgava, 8 December 1654. Transcript. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 431, p. 149.

The Hofmarschall or court-marshal, was one of the most senior officials, responsible for the functioning of the court. In his order, James instructs Sacken to particularly supervise the duke’s kitchens and drinks cellar, which included overseeing food preparation and cleanliness in the kitchen. The duke promised a wage of 600 guilders a year, free board for Sacken himself, two servants and two coachmen, and forage for six horses.

The court marshal was usually appointed from among the highest nobility, and in many cases this post served as a stepping-stone for advancing one’s career. For example, in 1656 Sacken became Captain or Hauptmann of Castle Neuhausen/Valtaiķi, and in 1666 he was made Supreme Captain or Oberhauptmann of Mitau/Jelgava.

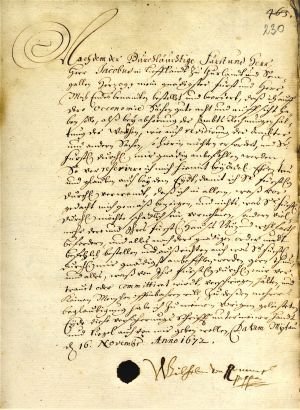

6. Oath of loyalty of Landsteward (Landhofmeister) Wilhelm von Rummel. Mitau/Jelgava, 16 November 1672. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 431, p. 230.

In terms of rank, the Landhofmeister was the first senior adviser and the head of the duchy’s government, usually appointed from among the other three senior councillors. It was a lifetime appointment. The Landhofmeister was also responsible for the economy of the duchy; he had to audit the duke’s estates and participate in checking the accounts of the estates. The Landhofmeister, like other senior councillors and members of the court, had to recite an oath of loyalty to the duke, but in some cases – as here – a written version was also added.

7. Instruction from Duke James on the appointment of the Chancellor of the duchy. Mitau/Jelgava, 6 November 1665. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 431, p. 226.

The chancellor was the second most important figure in the duke’s government or supreme ducal council after the Landhofmeister. When he took office, the chancellor had to swear an oath of loyalty to the duke and promise not to reveal secrets. He had to supervise the work of the chancellery and fulfil the tasks set by the duke. The chancellor received an annual sum of 1000 guilders, free board for himself, two servants and two coachmen, and forage for six horses. He also had a free apartment in the town of Mitau/Jelgava and a room in the castle. The chancellor was also the head of the consistory or court of the Evangelical Lutheran Church. The instruction was written at the time when Wilhelm von Rummel became chancellor; in 1672 the duke appointed him Landhofmeister.

As with other oaths given by officials, the chancellor would usually swear the oath after a set form. Accordingly, it is noted at the bottom of the document that on 14 February 1676 this oath was given by chancellor Ewaldt Franck, and on 14 February 1678 by Christoph Heinrich von Puttkamer. It must be noted that for many years Rummel also held the post of Duke James’s Hofmeister, while Puttkamer’s father had previously been Hofmeister to Louise Charlotte.

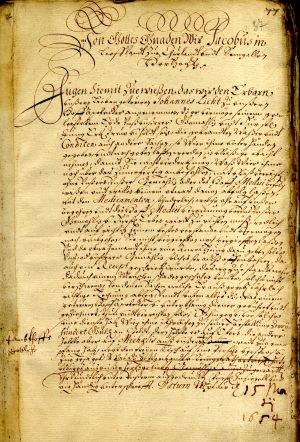

8. Instruction from Duke James on the appointment of Johannes Licht as court Apothecary (Hoffapotecker). Mitau/Jelgava, 15 March 1654. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 431, p. 37.

The court apothecary worked solely in accordance with the instructions of the duke, the duchess and the court doctor (Hof-Medicus). When preparing medicine for the duke and his family, the apothecary was to take care to avoid any risk of poisoning, check that the quantities of medicine indicated in the prescriptions were not too strong and harmful to their health, and was to account for the spirits, candied fruits, spices and other items in his charge. He was entitled to a wage of 200 guilders and free board.

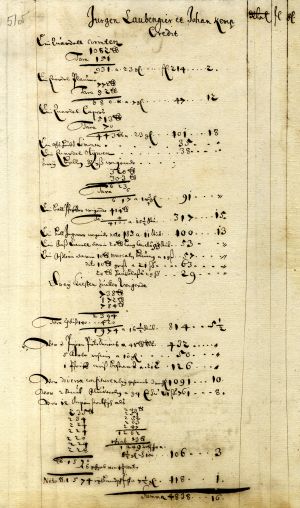

9. Invoice from Jürgen Laubengier and Johann Kempe, the duke’s factors or trading agents in Amsterdam. 1642/1643. Excerpt. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 83, p. 51.

The invoice reflects the consumption of various spices and delicacies at the court of Duke James. The items sent to the duke in the course of a year include five baskets of raisins, three boxes (827 kg in total) of sugar, 20 pounds (8.4 kg) of mace and an equal quantity of cinnamon sticks, 183 pounds (77 kg) of ginger, 931 pounds (390 kg) of serviceberries, 680 pounds (285 kg) of prunes, 410 pounds (172 kg) of pepper, as well as rice, olives, marmalade, lemons, etc.

Mace (Muscaten Blumen) refers to the husk of the nutmeg seed, which was used in dried form, either whole or ground.

10. Passport issued by Duke James to Joseph Woinicz to Transylvania. Mitau/Jelgava, 27 June 1656. In Latin. Transcript. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 1026, p. 20.

The passport states that it has been issued to Woinicz, so that he might bring the duke some barrels of Hungarian wine and several horses from Transylvania.

11. Instruction from Duke James to ship’s captain Jacob Dousen (also Dowessen). Grobin/Grobiņa, 2 November 1660. Transcript. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 265, p. 15.

James orders that a cargo be loaded in Amsterdam and taken to France, bringing the duke salt and 20 barrels of wine on the return journey. As soon as the ship reached Nantes or Bordeaux, word was to be sent, so that the duke might give instructions on transporting the chef (Küchenmeister) Noell and other hired staff.

12. Statement by the duke’s cook Jacob de Gardin (also de Gardein). Mitau/Jelgava, 4 January 1671. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 2057, p. 117.

Since Duke James has hired him as his chef (Mundt- und Meister Koch), de Gardin promises to serve him faithfully and asks for the amount of his wage to be recorded in a written document, which he would certify with his signature. Such a document was duly prepared. The duke would pay the cook an annual wage of 240 florins and promises to issue him a livery of the kind worn by the duke’s trumpeter as well as 60 ells of linen cloth and one oxhide, and to grant him free lodgings and firewood, and bread and beer from the duke’s cellars for the cook and his wife.

Unfortunately, the volume containing the contracts between James and various craftsmen has been badly damaged by water, and so a large proportion of the documents are hard to read or are completely illegible.

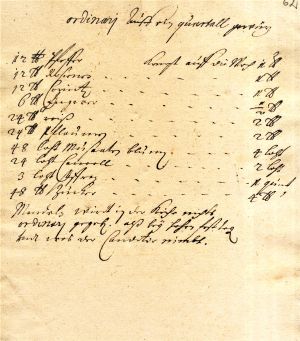

13. Instruction on the daily consumption of spices in the duke’s kitchens. Around 1675. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 60, p. 62.

The kitchen master issued to the court cooks the foodstuffs they needed for cooking meals, including spices, in specified quantities. In the course of a week, the duke’s kitchens required a pound (about 419 g) of pepper, and an equal quantity of raisins and serviceberries, half a pound of ginger, two pounds each of rice and plums, four pounds of sugar, four lots (about 53 g) of mace, two lots of cinnamon and a quarter of a lot of saffron. It is noted at the bottom that almonds were to be issued to the cooks for major feasts, but ordinarily they were to be provided only to the pastry cook.

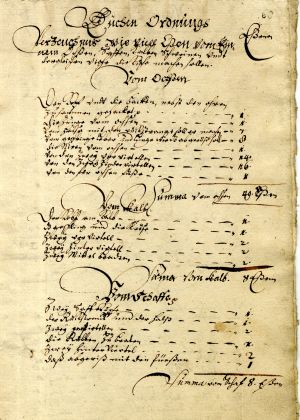

14. The duke’s kitchen regulations (Küchen Ordnung). Around 1661. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 60, p. 60.

The regulations indicate the quantities of food that were to be prepared for the table from particular kinds of produce. For example, one ox had to provide 49 meals or servings; a calf or sheep was to provide eight, a lamb six, a pig 30; eight herrings were to provide a single meal; a peck (c. 8 kg) of peas was to provide 16, and a barrel of Dutch herring was to provide 100; 1800 dried Baltic herrings were to provide 10 meals; a barrel of cheese 60, etc.

Regulations of this kind were common practice at the time, because in other courts, too, especially the smaller ones, much attention was given to supervising the handling of food and its rational consumption.

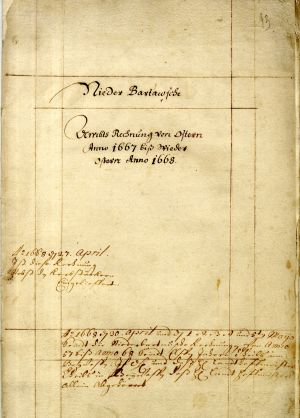

15. Annual accounts (Ambts Rechnung) of Niederbartau/Nīca estate, from Easter 1667 to Easter 1668. Excerpt. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 1456, pp. 93, 106.

Along with other incomes and expenditures, the accounts enumerate the produce sent during the course of the year to Mitau/Jelgava for the duke’s court: 22 bushel or Lof (c. 48 kg) of barley groats, four barrels of sauerkraut, two Lof each of carrots and parsley roots, three Lof of parsnips, eight Lof of turnips, seven bullocks, 84 live sheep, 18 lambs, six pig heads, 12 pieces of bacon, 6½ barrels of salt meat, eight tongues, three barrels of butter, 19 barrels of cheese, 20 pounds of wax, 147 chickens, 1231 eggs, 38 live geese as well as fish, game, etc.

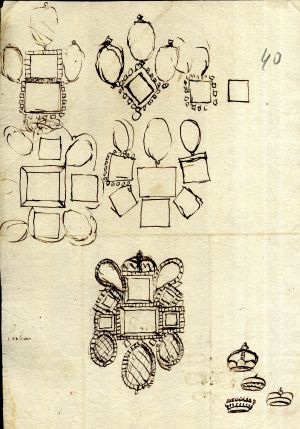

16. Sketches of jewellery from the archive of the Dukes of Courland. Mid-17th century. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 681, p. 40; ibid., file 856, pp. 63, 64; ibid., file 858, p. 134.

Duchess Louise Charlotte strove to follow the latest fashion trends as far as she could. She often consulted on such questions with her younger sister, Hedwig Sophie in Kassel, to whom she would often also send sketches of jewellery. The drawings that have ended up in the archive show pendants, brooches and earrings.

17. Drawing of a goblet. Second half of 17th century. LVVA, collection 1100, inventory 13, file 728, p. 132.

The goblet has been shaped to resemble the vessels made from marine mollusc shells that had become popular already in the 16th century. If indeed a vessel such as the one shown actually existed, then it would most probably have been made from gilded silver. Inventories of the property of the duke and duchess list large quantities of various silverware, even including a chamber pot, but this particular goblet is, unfortunately, not identifiable.

18. Small wine cask from the tableware collection of Duchess Louise Charlotte. Gilded silver. 1645. Hessisches Landesmuseum, Kassel. Photo: A. Hennsmann.

This little wine cask, 38 cm long and 35 cm high, was a wedding gift to Duke James and Duchess Louise Charlotte from the town of Libau/Liepāja. After the death of the duchess, along with many other items, it ended up in Kassel with her daughter Marie Amelie, as part of her inheritance.

19. List of leather wallpaper, signed by Duchess Louise Charlotte. 22 May 1665. LVVA, collection 1100, inventory 13, file 728, p. 27.

In 1665, the stocks of leather wallpaper were inspected. The list includes gilded and silvered as well as red, green and blue painted smooth and ornamented wallpapers, kept in boxes in the form of separate pieces. Some of these were from the great hall and the duchess’s apartments in Goldingen/Kuldīga Castle. These had possibly removed because the interiors of this castle were painted in 1665. Also enumerated is green and gold Dutch wallpaper from the hall of Mitau/Jelgava Castle, as well as red and gold wallpaper from Duke James’s rooms in Mitau/Jelgava Castle. Unfortunately, not one piece of leather wallpaper has been found in Latvia from that time; however, several examples of such Dutch wallpaper are kept in the German Wallpaper Museum in Kassel.

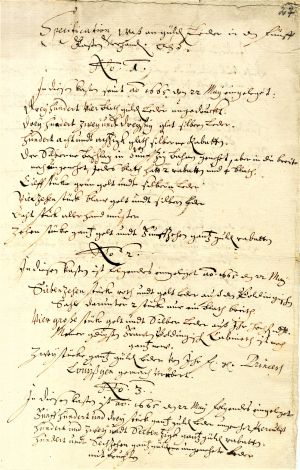

20. Lists of the duke’s books. 1648, 1656–1663. Excerpts. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 858, p. 234; ibid., inventory 3, file 56, pp. 48–51.

The library of the Dukes of Courland had one of the region’s largest book collections. Duke James and Duchess Louise Charlotte significantly augmented the collection created by their predecessors. The titles of the books purchased reflect their interests: thus, the duchess purchased religious works and literature on housekeeping and gardening, while James collected volumes on mathematics, engineering, life sciences, history, geography, politics and economics. For example, the catalogues include the “Book of Herbs” (Cruydt-Boeck) by Flemish botanist Rembert Dodoens, the work “The Royal Riding School” (Die Königlische Reitschuel) by Antoine de Pluvinel, riding instructor to Louis XIII of France, the “Collection of Treasures of Mechanical Art” (Schatz-Kammer Mechanischer Künste) by Italian engineer Agostino Ramelli, the “Description of ores” (Beschreibung allerfurnemisten Mineralichen Ertzt unnd Bergwercksarten...) by Lazarus Ercker, advisor on mining to Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, the “Book of fortifications” (Architectura Militaris nova et aucta, oder Newe vermehrte Fortification...) by Polish engineer Adam Freitag, etc.

Interestingly, Duke James may have been personally acquainted with Freitag, because, like James, in 1633–1634 he had taken part in the siege of Smolensk while serving in the army of Poland-Lithuania. From the 1640s until his death he had been the court doctor, mathematics teacher and fortification specialist of Prince Janusz Radziwiłł at Kėdainiai and Biržai.

21. Instruction from Duke Frederick Casimir to superintendent Heinrich Adolphi in connection with his father’s death. Mitau/Jelgava, 1 January 1682. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 39, p. 58.

In this instruction, Frederick Casimir states that his father, Duke James, has died at two in the afternoon of 31 December. Accordingly, the superintendent was to order the pastors in the duchy to hold memorial services in the churches, and to ring the church bells every day for a year and six weeks from midday until 1 p.m.

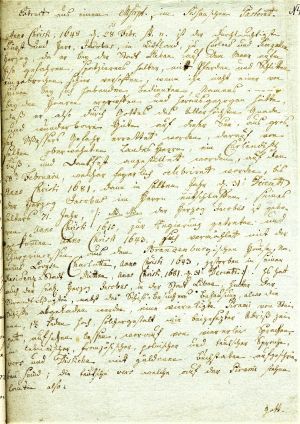

22. Description of the death and funeral of Duke James, compiled by secretary Georg Stephani. 1683. LVVA, collection 5759, inventory 2, file 1330, pp. 2–4.

The author records that in the years after his wife’s death James frequently suffered from ill health, and for this reason even executed a certain Magnus Lucht, Manager of ducal estate Neugut/Vecmuiža, who had been accused of having cast a spell on the duke. James hoped to recover by activity, so a few weeks before his death he visited his estates in Semigallia, but was soon forced to return. In the last moments of his life, he received Communion and blessed his sons Frederick Casimir and Ferdinand, who were with him. When he died, the duke’s body was first dressed in the fine dress in which he had been married, and was placed in an elaborate canopy bed. After two weeks the corpse was dressed in black velvet dress, placed in the coffin and transferred to the antechamber of the former apartment of the duchess. Up to Easter 1682, the supreme captains, captains and managers of domains were invited to Mitau/Jelgava, each in turn, to form a guard of honour by the coffin, after which they were replaced by four soldiers of the guard.

The funeral of the duke was held a year and a half later – on 21 September 1683. On the previous day, the coffin was brought to the castle hall (Rittersaal), which had been hung with black cloth. The funeral ceremony began with an address by Landsteward (Landhofmeister) Puttkamer; after this, the coffin was taken to the castle church in a solemn torchlight procession, where music was played and the court pastor Hollenhagen held a service of remembrance. Then the coffin was placed in the burial vault. That evening, the funeral feast continued until late in the night, attended by representatives of the nobility, while the town citizens and commoners among the officials dined in the chancellery and other rooms in the castle.

23. Monument erected in Libau/Liepāja, commemorating the rescue of Duke James after he fell through the ice on 28 February 1648. 19th-century excerpt from a manuscript kept at Sessau/Sesava pastorage. LVVA, collection 5759, inventory 2, file 167, pp. 6–7.

Duke James lived to be 71, which was a fairly advanced age for the time, but his life could have been cut short some years after he ascended the throne. Thus, on 28 February 1648, during a visit to Libau/Liepāja, James took a sleigh trip on the frozen sea and suddenly fell through the ice. He was saved from drowning by one of the servants, who caught the duke by his hair and pulled him from the water. To commemorate this event, a square stone pyramid about two and a half metres high was built on the shore between the residences of the shore bailiff and the ship inspector, on the faces of which a description of the event and a message of thanks to God for the rescue were carved in gold letters in Latin, French, Polish and German. Henceforth, right up to the duke’s death, special thanksgiving services were held in the churches on 28 February.

Unfortunately, the memorial has not been preserved up to the present day, but might be regarded as the earliest known secular monument in present-day Latvia.