Duke James was a gifted but contradictory figure. He had diverse interests and was very enterprising, but his ambitious plans often bordered on recklessness. Capable in engineering and technical matters, a loving husband and a strict father, he could be very kind as well as harsh and intolerant, and in implementing his plans he did not always consider the duchy’s financial possibilities. James was often excessively frugal and even miserly towards his servants and his own children; at the same time, he attached great significance to his honour as ruler and his personal prestige. James cannot be called a strong politician, but it should be borne in mind that his freedom of action was restricted not only by the mutual hostility between the neighbouring countries, but also by the constitution of the Duchy of Courland and the nobility’s resistance to any strivings by the duke to increase his power.

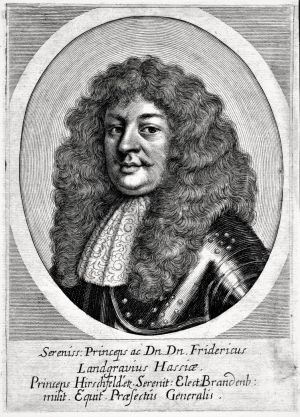

1. James, Duke of Courland and Semigallia (1610–1681). Engraving by Mathias Czwiczek. 1648. Wikimedia.

James was born in Goldingen/Kuldīga Castle on 28 October 1610, and was christened in the castle church on 23 December; three days later, his mother, Princess Sophie of Prussia (1582–1610), was buried in the same church. His father Duke William (1574–1640) transferred him in 1612 to the care of the relatives of his deceased wife in Königsberg and Berlin. James returned to Courland in 1624, and the years that followed were spent in an effort to regain his title as heir to the throne, which James had lost in 1616, when William had been removed from the throne. This was achieved in 1633. From autumn 1634 until February 1637 James travelled abroad, spending longer periods in Holland and France.

2. Duke James. Artist unknown. 1670s. Copy in Gripsholm Castle, Sweden. Photo from the archive of Bauska Castle Museum.

Before his marriage to Louise Charlotte (1617–1676), Princess of Brandenburg-Prussia, James had been rejected by three other candidates. But this can actually be considered rather fortunate, because the marriage to Louise Charlotte turned out to be a happy one. James’s family had dynastic links not only with Brandenburg-Prussia but also with Poland-Lithuania, Denmark, Mecklenburg, Hesse and other countries. Duke James was the maternal grandfather of King Frederick (Fredrik) I of Sweden.

3. Louise Charlotte (1617–1676), Princess of Brandenburg-Prussia. Engraving by Johann Hermann after a drawing by M. Czwiczek. 1643. Wikimedia.

Louise Charlotte was born on 13 September 1617, the eldest child of George William (Georg Wilhelm, 1595–1640), Elector of Brandenburg, and Elisabeth Charlotte of the Palatinate. For the whole of her lifetime, Louise Charlotte maintained close ties with her brother Frederick William (Friedrich Wilhelm, 1620–1688), Elector of Brandenburg, known as the “Great Elector”, and her sister Hedwig Sophie (1623–1683), who married to become Landgravine of Hesse-Kassel.

In the engraving, the princess is shown in mourning, because her betrothed – Ernst, Margrave of Brandenburg-Jägerndorf – had died in 1642. Louise Charlotte did not marry Duke James out of love, but over the years she became strongly attached to her husband.

4. Louise Charlotte, Duchess of Courland. Artist unknown. 1670s. Copy in Gripsholm Castle, Sweden. Photo from the archive of Bauska Castle Museum.

James and Louise Charlotte had 11 children, but only seven of them reached the age of 20. The duchess was a caring mother and enjoyed relationships full of sincerity with her children right up to her death on 18 August 1676.

5. Louise Elisabeth (1646–1690), Princess of Courland, Landgravine of Hesse-Homburg. Artist unknown. 1670s. Copy in Gripsholm Castle, Sweden. Photo from the archive of Bauska Castle Museum.

Duke James’s eldest child Louise Elisabeth was born in Mitau/Jelgava on 12 August 1646. She was brought up in Courland, and Duchess Louise Charlotte took charge of her education. Along with the rest of the family, she was imprisoned by the Swedes (1658–1660). In 1666, Michał Korybut Wiśniowiecki, the future king of Poland-Lithuania, wished to ask for her hand in marriage, but the duke did not want a Catholic son-in-law. In Berlin on 23 October 1670 she married Frederick II (Friedrich II. von Hessen-Homburg, 1633–1708), Landgrave of Hesse-Homburg. The marriage, a happy one, produced 12 children.

6. Plaque with the street name Louisenstraße (Louise Street) in Bad Homburg, former capital of the Landgraviate of Hesse-Homburg. Photo: Mārīte Jakovļeva.

The street is named after Louise Elisabeth, daughter of Duke James, as indicated by the lower plaque, giving the life dates of the duchess and the information that she was the niece of the “Great Elector” of Brandenburg and the second wife of Landgrave Frederick II.

7. Frederick II (1633–1708), Landgrave of Hesse-Homburg, husband of Louise Elisabeth, Princess of Courland. Engraving after a painting by an unknown artist. 1670s. Wikimedia.

Landgrave Frederick had lost his right leg up to the knee in a battle in 1659, but this did not stop him from continuing his successful military career. In 1672, he became commander-in-chief of the army of Brandenburg. In the first years of their marriage, Louise Elisabeth would often accompany her husband on his campaigns. After the death of his elder brother, Frederick took over Homburg in 1681 and built a splendid Baroque palace. The court alchemist made him a prosthesis with silver hinges, and Frederick became known by the nickname “the Landgrave with a silver leg”. Frederick was very fond of his wife and would address her by pet names in his letters: “my darling roly-poly”, “my plump angel” and so forth.

8. Frederick Casimir (1650–1698), Prince of Courland and heir to the throne. Artist unknown. 1670s. Copy in Gripsholm Castle, Sweden. Photo from the archive of Bauska Castle Museum.

Frederick Casimir was born in Mitau/Jelgava on 6 July 1650. After the family returned from Swedish captivity, his mother took him to Berlin to stay with his uncle, the Elector of Brandenburg, and here he remained for seven years. In 1666, James wished to send him to study in Poland, but the elector objected. In 1668, Frederick Casimir went to study in Paris, and in late 1671 returned to Courland. In return for payment, Duke James permitted the Dutch to recruit four regiments in the duchy in 1672, commanded in battle by Frederick Casimir. As long as Brandenburg was an ally of the States General of the Netherlands, the elector had no objection to this, but soon afterwards the elector concluded a separate peace with France and altered his stance. The King of Poland also began to express his dissatisfaction with James’s assistance to the Dutch. Accordingly, James strove to recall his son from military service, and in his correspondence with foreign countries he dissociated himself from his son’s activities. Frederick Casimir stayed in Holland up to the end of 1676, when he returned to Courland and joined the administration of the duchy. In 1677, he re-established the shipyard in Libau/Liepāja.

9. Sophie Amelie (1650–1688), Princess of Nassau, first wife of Frederick Casimir, Prince of Courland. Artist unknown. 1670s. Copy in Gripsholm Castle, Sweden. Photo from the archive of Bauska Castle Museum.

Sophie Amelie and Frederick Casimir were married in Hague on 5 October 1675. Like Duchess Louise Charlotte, she was a Calvinist. Sophie Amelie arrived in Courland with her husband in late 1676, and their marriage contract was concluded on 27 September 1678. This marriage, too, may be said to have been a happy one.

10. Charlotte Sophie (1651–1728), Princess of Courland, later Abbess of Herford. Artist unknown. 1670s. Copy in Gripsholm Castle, Sweden. Photo from the archive of Bauska Castle Museum.

Charlotte Sophie was born in Mitau/Jelgava on 1 September 1651. When the family returned from Swedish captivity, her mother sent her, along with her two brothers, to Berlin, where she was brought up by Louise Henrietta, wife of the elector. Charlotte Sophie returned to Courland in 1668. Several different marriage plans were made for her, but she remained unmarried. In 1678 she went to Kassel to her aunt, Hedwig Sophie and her sister Marie Amelie. In 1688 she was elected Abbess of Herford Abbey (Frauenstift Herford), where she had the status of Princess of the Holy Roman Empire.

11. Marie Amelie (1653–1711), Princess of Courland, Landgravine of Hessen-Kassel. Artist unknown. 1670s. Copy in Gripsholm Castle, Sweden. Photo from the archive of Bauska Castle Museum.

Marie Amelie was born in Mitau/Jelgava on 12 June 1653. Together with her family, she was in Swedish captivity, and grew up with her mother in Courland. Already in 1667, it was agreed that she would marry her cousin, William (Wilhelm VII.), Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel, and in 1669 Marie Amelie went to Kassel. While the bridegroom was travelling Europe on his “cavalier’s tour”, it seems she was diligently engaging in French, arithmetic and Bible studies. However, William fell ill and died in Paris during his travels. Marie Amelie stayed in Kassel, and in May 1673 married William’s brother, the Landgrave Charles (Karl von Hessen-Kassel, 1654–1730). The marriage was a success, and their son Frederick became King of Sweden in 1720. Several buildings in Kassel were erected thanks to Marie Amelie; she also left an impressive porcelain collection, which is preserved up to the present day.

12. Charles (1654–1730), Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel, husband of Marie Amelie, Princess of Courland. Engraving after a painting by an unknown artist. Around 1700. Wikimedia.

Landgrave Charles improved the financial situation of Hesse-Kassel through the large-scale recruitment of soldiers in return for foreign subsidies. Apparently, he had become enamoured of Marie Amelie at the time when she was still his elder brother’s fiancée.

13. Charles James (Karl Jacob, 1654–1676), Prince of Courland. Artist unknown. 1670s. Copy in Gripsholm Castle, Sweden. Photo from the archive of Bauska Castle Museum.

Charles James was born in Mitau/Jelgava on 20 October 1654. Together with his brothers and sisters, he experienced Swedish captivity, and after their return he and his brother Ferdinand were brought up in Courland. In about 1669 the duke sent Charles James to study abroad. He spent some time in Italy and then studied in Switzerland, where in 1663 he complained to his mother that he was embarrassingly short of money, on account of which he could not avoid falling into debt. Soon, at the urging of his aunt Hedwig Sophie, Charles James joined the Dutch army, but the duke recalled him from service for political reasons, threatening to deprive him of his inheritance. On the way to Courland, Charles James caught typhus in Berlin and died on 29 December 1676.

14. Ferdinand (1655–1737), Prince of Courland. Artist unknown. 1670s. Copy in Gripsholm Castle, Sweden. Photo from the archive of Bauska Castle Museum.

Ferdinand was born on 2 November 1655. He was raised together with his brother Charles James, who was one year older. In 1674, Ferdinand went abroad, to Poland, Austria and Italy, and in 1677 he spent ten months in Geneva, where he got into trouble because of a quarrel with the son of Baron von Friesen. Without informing his father, he left Switzerland for Paris, to James’s great displeasure. The duke wished Ferdinand to go to England and then take over Tobago, or else to Spain to learn the language, which would likewise be useful in the administration of the colonies. However, he disobeyed his father and joined the military instead. Ferdinand spent the whole of his life in the army until the death of his elder brother Frederick Casimir, when he became the ruler of the duchy. Ferdinand was the last surviving male descendant of the family line of the Dukes Kettler.

15. Alexander (1658–1686), Prince of Courland. Artist unknown. 1670s. Copy in Gripsholm Castle, Sweden. Photo from the archive of Bauska Castle Museum.

Alexander was born on 18 October 1658, one week after the Swedes had taken Mitau/Jelgava Castle. After Swedish captivity, his mother sent him at the age of less than three years together with his elder brother and middle sister to be placed in the care of the Elector of Brandenburg, where conditions were much better than in the war-ravaged duchy. Alexander came back to Courland in 1668, but in 1677, against the wishes of the duke, he returned to the elector, with whom he had a warm relationship. Even though Alexander was born without his right forearm, this did not prevent him from becoming a good soldier. Unfortunately, on 16 August 1686 he died from wounds sustained in a battle at Buda/Ofen (Hungary).

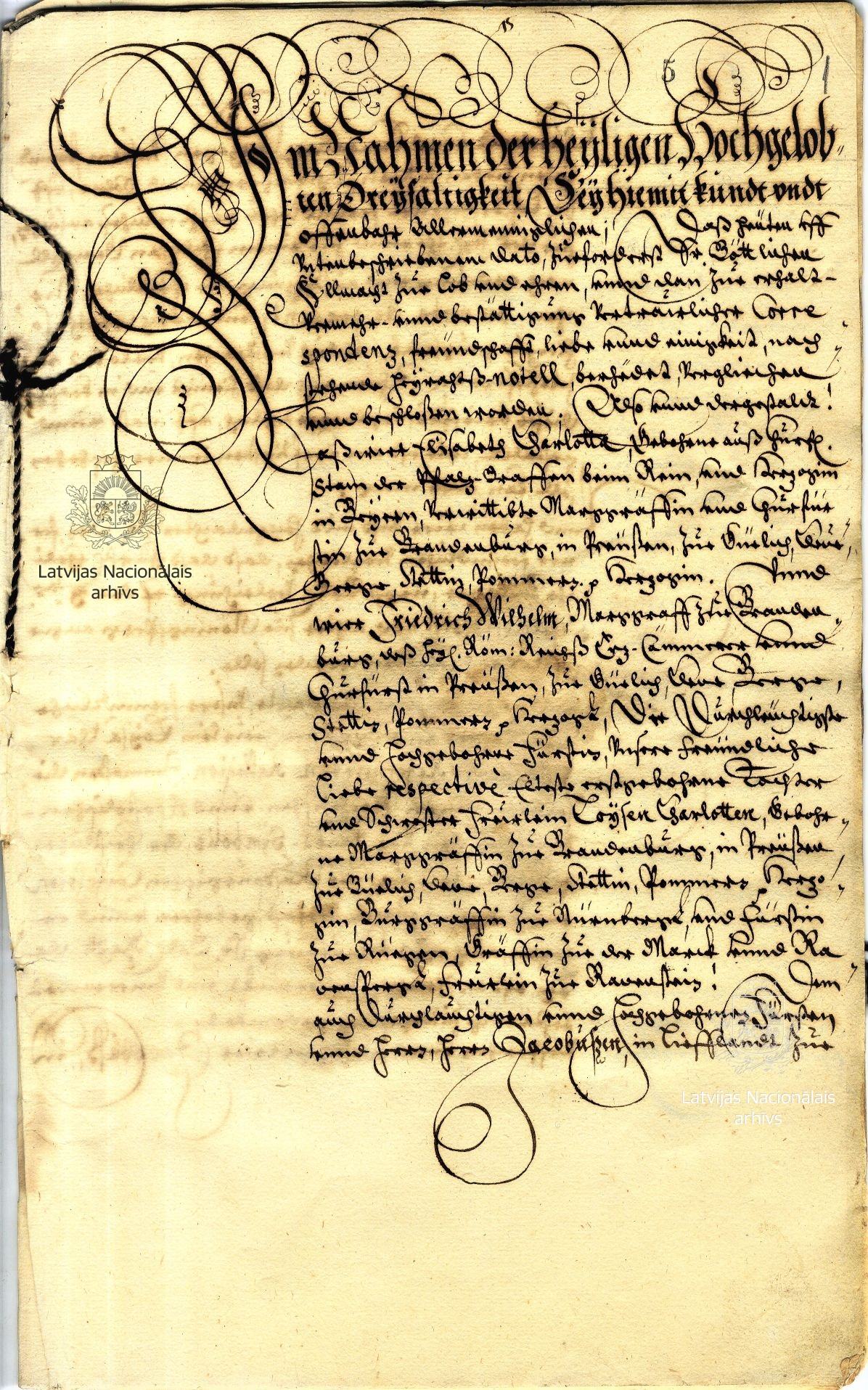

16. Marriage contract between James, Duke of Courland, and Louise Charlotte, Princess of Brandenburg-Prussia. Königsberg, 13 July 1645. First and last page. With the signatures of Duke James, the princess’s mother Elisabeth Charlotte, Electress of Brandenburg, and her brother Elector Frederick William. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 770, pp. 1–13.

In accordance with the contract, Louise Charlotte was to have a dowry of 15,000 thalers as well as valuables and silverware (worth 21,500 thalers). For his part, James promised a capital of 10,000 as a wedding gift (Morgengabe), of which the duchess should receive 1000 thalers a year as interest. In the case of the duke’s death, the widow was to reside at the castle of Grobin/Grobiņa or Schrunden/Skrunda. James allotted the income from the estates of Grobin/Grobiņa, Oberbartau/Bārta and Rutzau/Rucava to support his wife’s court. Likewise, the duke guaranteed Louise Charlotte the right to remain a Calvinist and raise her children in the faith up to the age of seven. From then on, the sons were to be raised as Lutherans.

James and Louise Charlotte were married in Königsberg on 10 October 1645. After eleven days of wedding celebrations, the young couple went to Goldingen/Kuldīga, where the festivities continued for another week. The newlyweds arrived in Mitau/Jelgava on 8 January 1646.

17. Johann Christian Borre. Eulogy for Duchess Louise Charlotte: the poem Laurel Wreath for the Duchess (Fürstlicher Lorber-Krantz). Around 1650. LVVA, collection 7363, inventory 3, file 910, p. 2.

In the introduction to the poem, the author refers to himself as coming from Leipzig, but unfortunately we lack information concerning his connection with Louise Charlotte. The duchess had been educated in accordance with the demands of the age, was active in economic matters, took an interest in politics, and loved reading and music-making. She was personally acquainted with the renowned German poet of the time Simon Dach (1605–1659), who was poetry professor and rector of Königsberg University and had the favour of the Elector of Brandenburg.

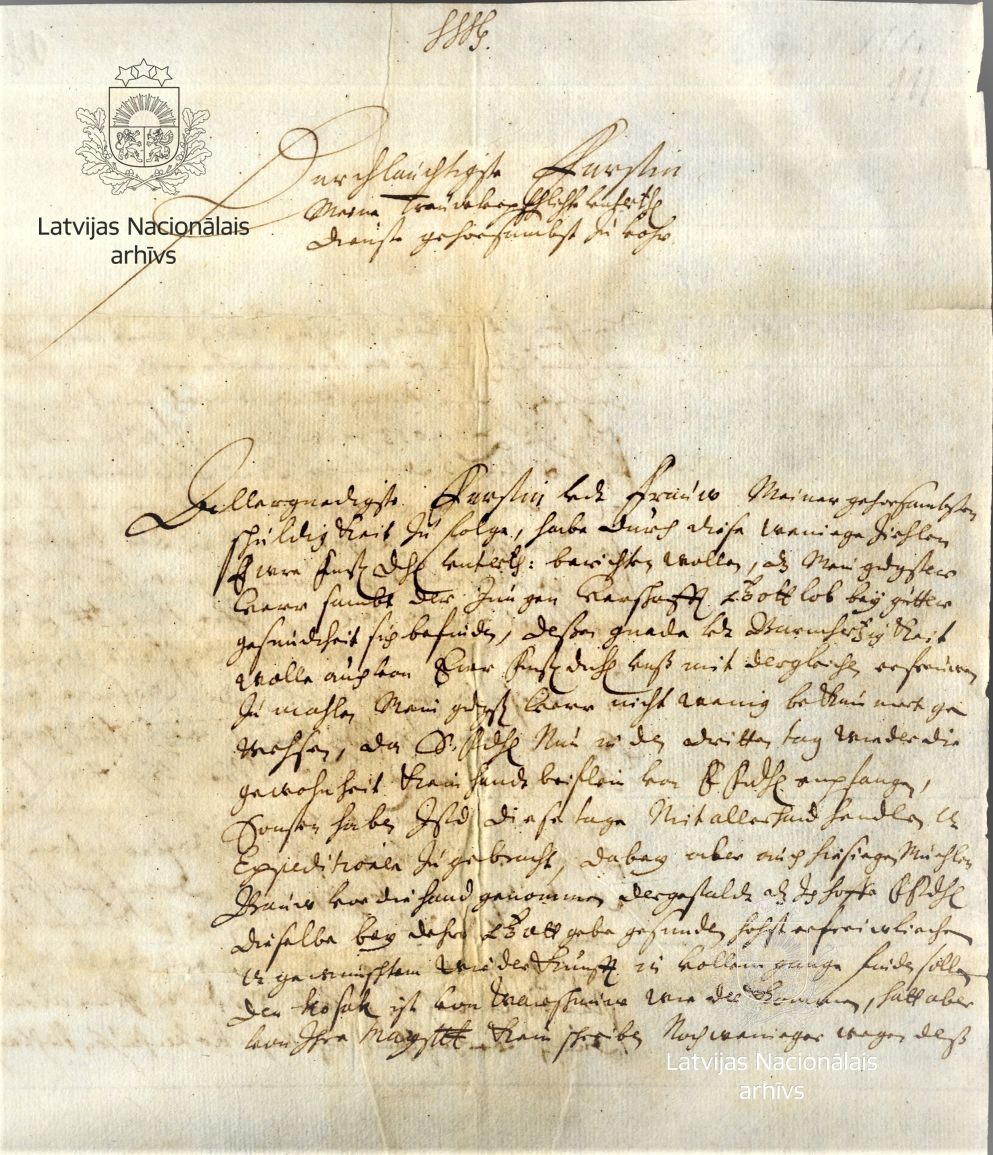

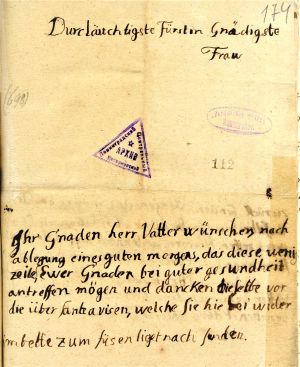

18. Letter from Melchior von Folckersamb, Chancellor of the Duchy, to Louise Charlotte. Grobin/Grobiņa, 23 August 1660. LVVA, collection 1100, inventory 13, file 720, pp. 111, 112.

Folckersamb reported to the duchess that the duke and the children who remained at home were well, but that James was concerned, because he had not received a single letter from her for three days. The duke was busy with various matters, including the building of a local mill. The chancellor also describes the political and military situation in the duchy and at its borders.

Soon after returning from Swedish captivity, the duchess left for Germany with three of her children to attend her mother’s funeral. Although at the time the letter was written Louise Charlotte had been away less than two weeks, the duke was already concerned at the lack of correspondence from her.

19. Letter from Charlotte Sophie, Princess of Courland, to Duchess Louise Charlotte. Berlin, 13 March 1663. LVVA, collection 7363, inventory 3, file 997, pp. 21, 22.

In her letter, the twelve-year-old princess thanks her mother for the money she had sent, because she has very many needs, and promises to take better care of her clothes. She also describes how the previous day she visited the elector, and that there was dancing on that occasion.

Charlotte Sophie and her brothers Frederick Casimir and Alexander spent seven years at the court of the Elector of Brandenburg, returning to Courland in 1668, once peace had finally come to the lands surrounding the duchy.

20. List of linen fabrics sent by Louise Charlotte, Duchess of Courland, to her children in Berlin. 11 March 1665. LVVA, collection 1100, inventory 13, file 728, p. 25.

According to the list, the eldest son was sent 36 ells of Dutch linen fabric, intended for six overshirts, as well as eight ready-made undershirts. Also listed is ordinary linen cloth for shirts, socks and pillowcases, sent to all three children in Berlin: the sons Frederick Casimir and Alexander, and the daughter Charlotte Sophie.

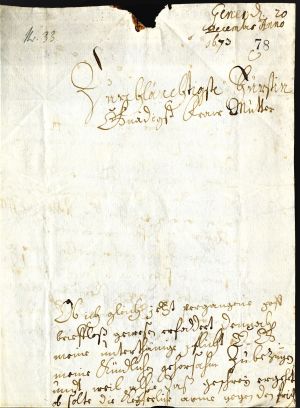

21. Letter from Charles James, Prince of Courland, to Duchess Louise Charlotte. Geneva, 20 December 1673. LVVA, collection 7363, inventory 1, file 654, pp. 78, 79.

Charles James asks his mother permission to travel to Burgundy together with the Prince of Württemberg in spring, to view the arrival of the emperor’s army. They also wish to view the carnival procession, which is to be held only two days drive from Geneva. Awaiting his mother’s reply, the prince sends his greetings to his father, sisters and brothers.

22. Letter from Alexander, Prince of Courland, to his mother. Undated [winter 1668]. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 269, pp. 174, 175.

Although Alexander had no right forearm, he wrote his own letters. In this letter the prince expresses his thanks in the name of his father for the newspapers, i.e. news sheets, that the duchess had sent, and writes that the duke is planning to go to Eckendorf/Ozolmuiža the next day and then proceed to Windau/Ventspils. The prince also relates that, in accordance with the duchess’s request, the duke has agreed to grant a minor position to an unnamed servant, even though the man is hardly able to mount a horse because of his age.

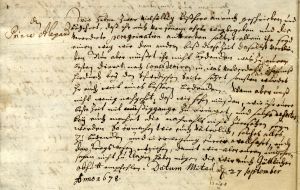

23. Letter from Duke James to Prince Alexander. Mitau/Jelgava, 27 September 1678. Transcript. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 449, p. 7.

In the letter the duke repeats the instruction he had given Alexander several times before to leave Berlin and go on a so-called cavalier’s tour, and complains that his son is not thinking of his future or considering the suspicious position in which he is putting his father in the eyes of the Swedes. Accordingly, the duke insistently urges Alexander to refrain from joining the army.

James was concerned that the news that Alexander had joined the army of Brandenburg, which was fighting against Sweden at the time, could have unwelcome consequences for the duchy. However, the son did not obey his father’s instruction and became an officer. Even though James wished his sons to refrain from military service, they all sought to embark on a military career.

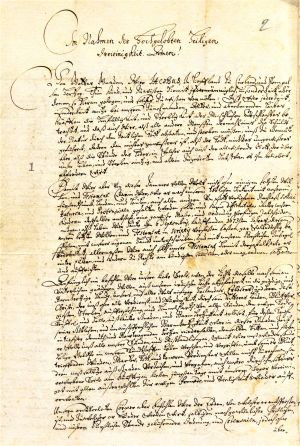

24. The will of Duke James. Mitau/Jelgava, 6 September 1673. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 285, pp. 2–4.

In his will, James left instructions that his body be placed in the burial vault of Mitau/Jelgava Castle in accordance with the ceremonial appropriate to his rank as duke but without undue expense. He appointed his eldest son Frederick Casimir as sole heir to the throne. The duke bequeathed his possessions in Sweden, Denmark and Pomerania to Charles James; to Ferdinand he bequeathed Tobago and Gambia, as well as 10 ships; Alexander had to be content with the properties promised by the Elector of Brandenburg. However, until such time as the possessions abroad should became accessible, the eldest son was also to maintain his three younger brothers from the duchy’s income, paying each of them 10,000 thalers a year, and was to help Ferdinand regain Tobago and Gambia. James also instructed Frederick Casimir to undertake what he himself had not managed in his lifetime, namely to recover the foreign debts: 50,000 thalers from Mecklenburg, 120,000 from Spain, 45,000 from Portugal and 500,000 from England, from which 100,000 thalers were to be paid to each of the sisters. The moveable property and money were to be divided equally between all of the children.

After the death of his wife and his son Charles James, on 31 March 1677 Duke James signed a Codicil to his will, in which he bequeathed to his children equal shares of the inheritance he had previously left to his wife, while the possessions due to Charles James, including the mines in Norway, were to go to Prince Alexander.

25. Sketch for a design of Durben/Durbe Church by Duke James. Goldingen/Kuldīga, 22 December 1645. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 437, p. 53.

Duke James had a great interest in engineering work and the building of various structures, especially in the first period of his rule. It is known that James himself also planned the alterations carried out on the fortifications of Mitau/Jelgava Castle. James placed Johann Pietzsch, the manor manager (Amtmann) of Durben/Durbe, in charge of the construction of the Church, begun in 1646. He was to report to the duke every week on the progress of the work. The duke calculated that the structure would require 100 lasts of lime, 120 beams, 300 boards, 50 boulders, etc. The church was consecrated in early 1651, and in spring 1652 James ordered the roof to be plastered with lime once again.

At the present day the church no longer has the Baroque tower designed by Duke James, but the overall form of the building has been retained.

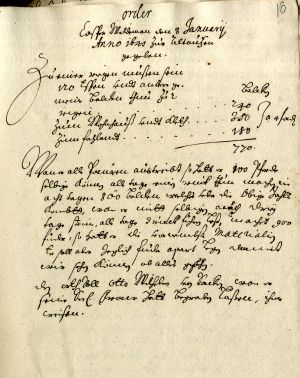

26. Instruction from Duke James to Caspar Wildemann, manager of the estate of Alt-Autzen/Vecauce. 8 January 1645. Transcript. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 437, p. 16.

This document, too, attests to the personal concern with all the details of economic affairs that was characteristic of Duke James. Thus, the duke lists the numbers of logs required for the construction of two threshing barns, a house, a storehouse and a barn. The two threshing barns together would need 240 logs, the house and storehouse 350, and the barn 180. James considered that the estate manager would be able to supply 800 logs in a hundred wagonloads brought by the peasants in eight days. The 900 loads of stone needed for the building work could be supplied in three days, if each waggoner made three trips a day.

27. Letter of guarantee from Courland Lutherans superintendent Paul Einhorn and Libau/Liepāja merchant Peter Batten to Duke James. Mitau/Jelgava, 19 August 1651. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 199, p. 11; promissory note (Obligation) from Christopher Reinhold von der Osten, called Sacken, to the duke. Mitau/Jelgava, 28 August 1663. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 228, p. 10.

James was very scrupulous in financial matters and would see to it that his officials handed over all of the money payable to the duke’s treasury. He was rather harsh on debtors; for example, the book of rulings from 1657 records the duke’s decision that, if the clerk of an estate were to die owing the duke more than 1000 florins, then until the debt was settled his heirs were forbidden to bury him with the appropriate ceremony (Leich- und Lobpredigt), but if it had been done all the same, then the body was to be exhumed immediately and they were to await further instructions from the duke. In many cases, the duke would have indebted officials arrested, as exemplified by the letter of guarantee from superintendent Einhorn and merchant Batten to James, in which they thank him for releasing Johann Pietzsch, the former manager of the Durben/Durbe and Tadaicken/Tadaiķi estates, promising that Pietzsch would pay his debt into the duke’s treasury without delay.

In the case of debtors belonging to the nobility, the duke would not have them arrested; instead, he would have them sign promissory notes in the presence of witnesses, as in the case of Sacken, manager of Oberbartau/Bārta estate: when the accounts were checked, a shortfall of 530 florins 18 groats was discovered for the period 1656–1663. Sacken undertook to pay the money within two weeks; otherwise the sum would be doubled.

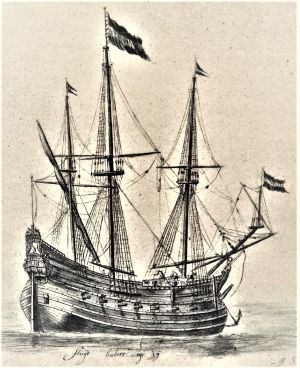

28. A fluyt. Illustration from the collection of Duke James. Drawing by Johann Streck. First half of 17th century. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 850d.

Shipbuilding and shipping can be said to have been a true passion of Duke James. While in Holland, James had also become acquainted with the latest Dutch achievement – the fluyt. In the first half of the 17th century, the fluyt became one of the most popular types of merchant vessel in the region. The duke, too, began building ships of this type. The drawings of ships preserved in the archive were brought to Courland either by the duke himself or by one of the Dutch shipbuilders he had invited. The illustrations of ships served as the designs followed by the shipbuilders. The drawings may have belonged to James’s library.

29. Model of an “amazing” ship built in Rotterdam. 1653. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 1, file 850d.

Duke James had a lifelong interest in world events. So that he might receive information, the duke maintained representatives and correspondents in many places, who would send him reports and news sheets with news from the West and East. Thus, in 1653 a strange ship aroused great public interest in Europe. The vessel was intended as a Dutch superweapon in the naval war between the English and Dutch (1652–1654). The ship was designed by the French inventor De Son (also Desson, Lisson), who declared that it would be the world’s strongest ship. It was to move partially underwater and without sails, but the designer would not reveal the details of the means of propulsion to anyone. While it was being built, the shipyard in Rotterdam became a real tourist attraction, and the subject of reports by spies and newspapers. However, the ship was never finished. In 1654 the warring sides made peace, and the unfinished structure was sold as firewood.

30. Instruction from Duke James to Fabian Friedlein, manager of Grossbuschhof/Birži manufactory. Mitau/Jelgava, 20 December 1676, with a sketch for an hourglass drawn by the duke himself. LVVA, collection 554, inventory 3, file 1798, pp. 1, 2.

The instructions that James issued were often very harsh. One such instruction was addressed to Friedlein, who managed the ironworks and glassworks established on the estate of Grossbuschhof/Birži not far from Jacobstadt/Jēkabpils. In response to a report explaining that iron production had been delayed because of the cold weather, James ordered that work must continue, since it was possible to work no matter how cold it was: they had only to cut free from the ice the waterwheel that drove the bellows and hammer. Otherwise, Friedlein would soon lose his post as manager. He also had to make sure the glassmakers did not take on work from other customers and worked only for the duke. James also ordered the production some hourglasses (about 120), urgently needed for ships, in accordance with the attached drawing.